Overview of Multinationals

Anyone who had predicted 15 years ago that Spanish companies today would own the largest mobile telephone company (O2) in the UK, operate several lines of the London underground and some of the country’s largest airports (including Heathrow), acquire three banks (Abbey, Bradford & Bingley and Leicester & Alliance) and a power company (Scottish Power), or that the two largest banks, Santander and BBVA, would generate more profits in Latin America than in their home county and Inditex would be one of the world’s two biggest clothes makers would have been laughed at for making an absurd joke. But this is precisely what has happened, and it is only a small part of the overall picture.

While the influx of immigrants is the most significant inward factor during this period, the most important outward factor is the massive investment abroad by Spanish companies and with it the creation of multinationals. Spain, along with South Korea and Taiwan, has produced the largest number of truly global multinationals among the countries that in the 1960s had not yet developed a solid industrial base. There is also a host of small and successful ‘pocket-sized’ multinationals.

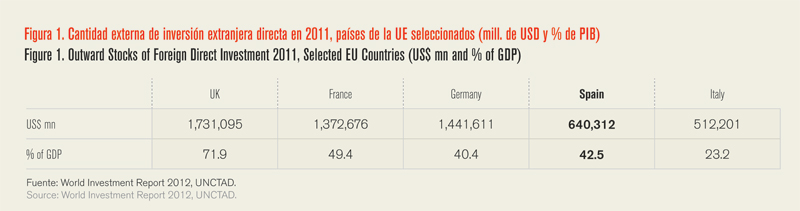

The stock of Spain’s outward investment stood at US$640.3 billion at the end of 2011 compared with a stock of inward investment of US$634.5 billion. In GDP terms, Spain’s stock of outward investment soared from 3.0% in 1990 to 42.5% in 2011, higher than Italy’s in relative and absolute terms (see figure 1), while the stock of inward investment over the same period increased from 12.5% to 42.5% of GDP.

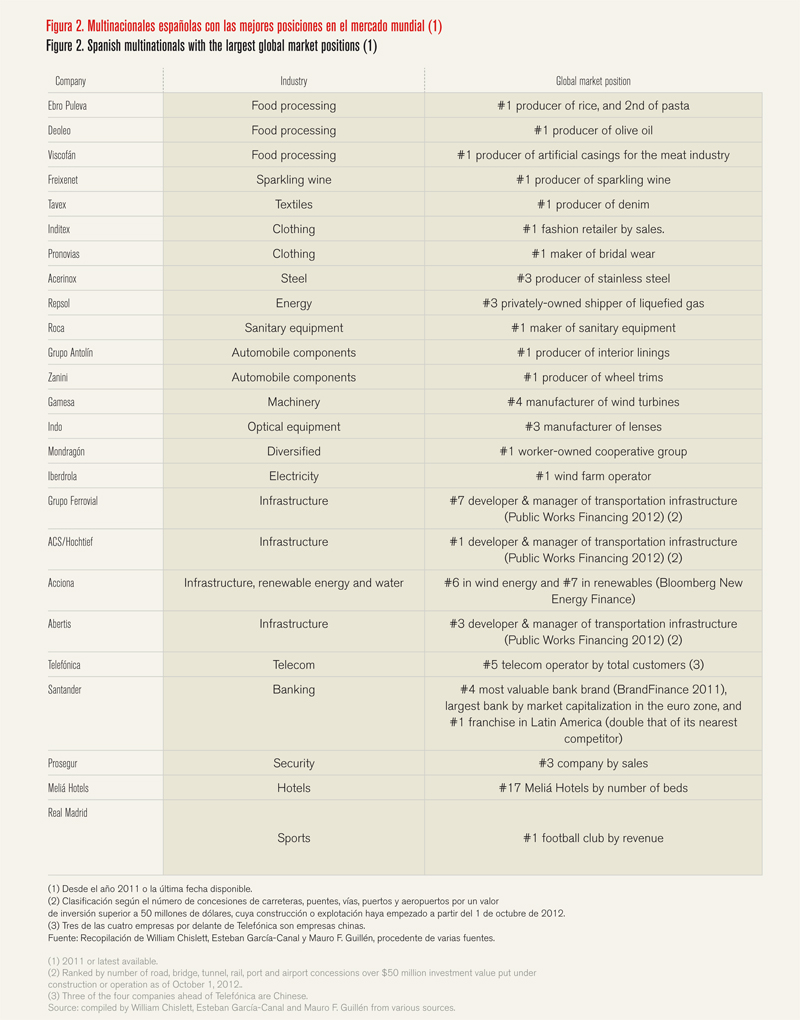

Some 25 companies have leading positions in the global economy in their respective fields (see figure 2), and two of them, Zara, the flagship of Inditex, and Santander, are among the 100 most valuable brands in the world (see figure 3).

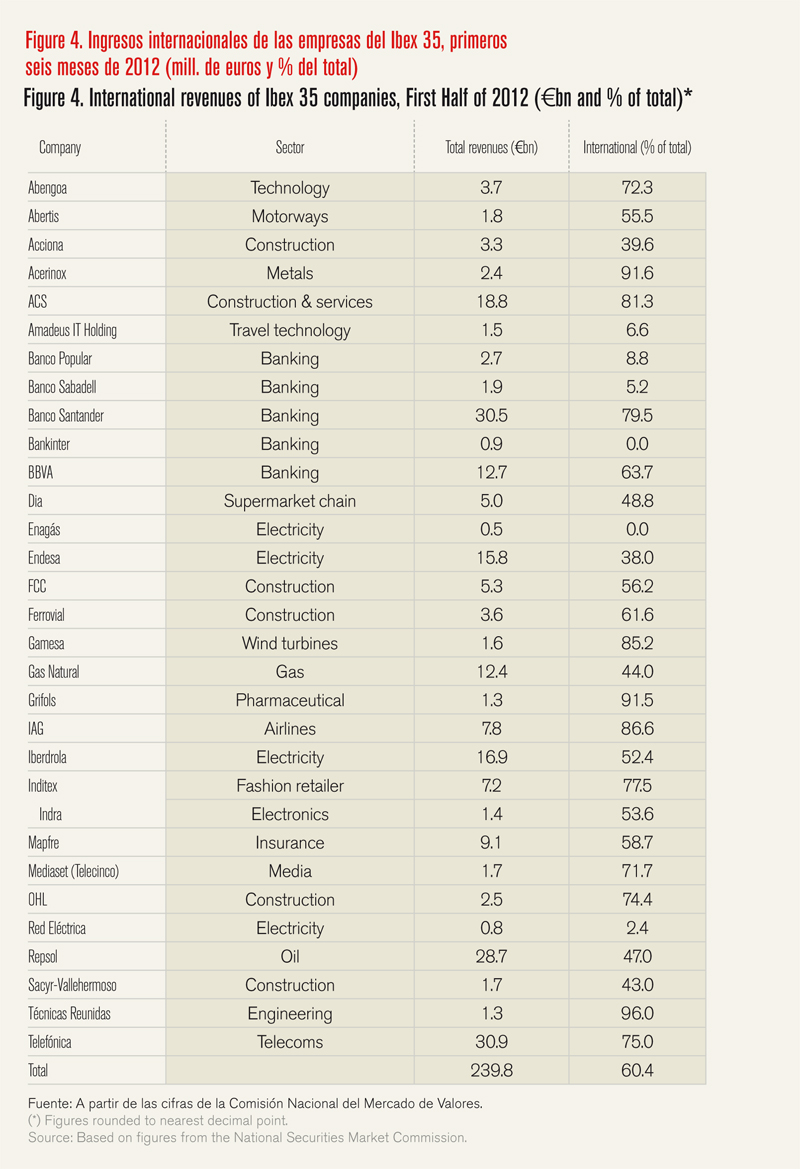

More than 60% of the revenues of the companies that comprise the Ibex-35, the benchmark index of the Madrid stock exchange, were produced abroad in the first half of 2012 (see figure 4). Thanks to their geographic and business diversification, these companies were able, to varying degrees, to offset the decline in business in the depressed Spanish economy. Acerinox (stainless steel) generated 92% of its revenues abroad, AcS (construction) 81% and Santander 80%.

Santander and BBVA are among the world’s top 50 financial transnational corporations (Tncs), with 407 and 142 foreign affiliates respectively, according to the 2012 World Investment Report of UncTAD, while four companies – Telefónica, Iberdrola, ferrovial and Repsol YPf– are ranked among the world’s top 100 non-financial Tncs. The financial Stability Board included Santander and BBVA in its updated list of the world’s systemically most important banks.

The Paradox of Exports

The Spanish economy has been losing competitiveness over the last few years, in terms of costs, prices and productivity, and yet the performance of exports has been surprisingly positive. Between 2009 and 2011 exports of goods rose by €54.6 billion to €214.5 billion (20% of GDP), an improvement equivalent to 5.1% of GDP and a faster pace of growth than Germany, france and Italy, albeit from a smaller volume. Merchandise exports represented around 22% of GDP in 2012, up from 18% decade earlier (See the author’s analysis of exports at http://www.realinstitutoelcano.org).

Recession at home or very low growth in the last four years has pushed companies into seeking markets abroad. exports of goods grew 15.4% in 2011 to €214.5 billion, compared with 11.4% growth in Germany and Italy and 7.5% in france, and imports 9.6% to €260.8 billion, reducing the trade deficit by 11.4% to €46.3 billion (0.5% of GDP compared to 5.8% in 2008). The main reason for Spain’s continued high trade deficit is the energy bill. The trade balance with the eU registered a surplus of €4.06 billion in 2011 compared with a deficit of €4.19 billion in 2010. There was also a surplus with the euro zone of €1.66 billion. These were the first surpluses since Spain joined the eU in 1986. In 2011, 122,987 companies exported, the largest number ever and 14% more than in 2009.

While the US, the UK, Germany, france and Italy have lost global market share to varying degrees over the last decade, mainly to china and other emerging countries, Spain’s share of world merchandise exports has remained virtually unchanged at around 1.7% (see figure 5), according to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Spain only lost 0.4 pp of its global share since its peak of 2.0% in 2004 compared with Germany’s 1.9 pp since 2004, the US’s 3.9 pp since 2000, france’s 1.6 pp since 2004 and Italy’s 0.9 pp.

One factor behind this apparently mysterious performance is that the cumulative loss of competitiveness has affected the export sector less as it has to be more efficient than the purely domestic sector in order to compete. exporters have also reduced their profit

margins in order to compete more strongly and enhanced the quality of their products. Spain, however, is still not a strong exporter, as figure 6 shows, although the volume of goods sold abroad rose from $55.6 billion in 1990 to $298.2 billion in 2011.

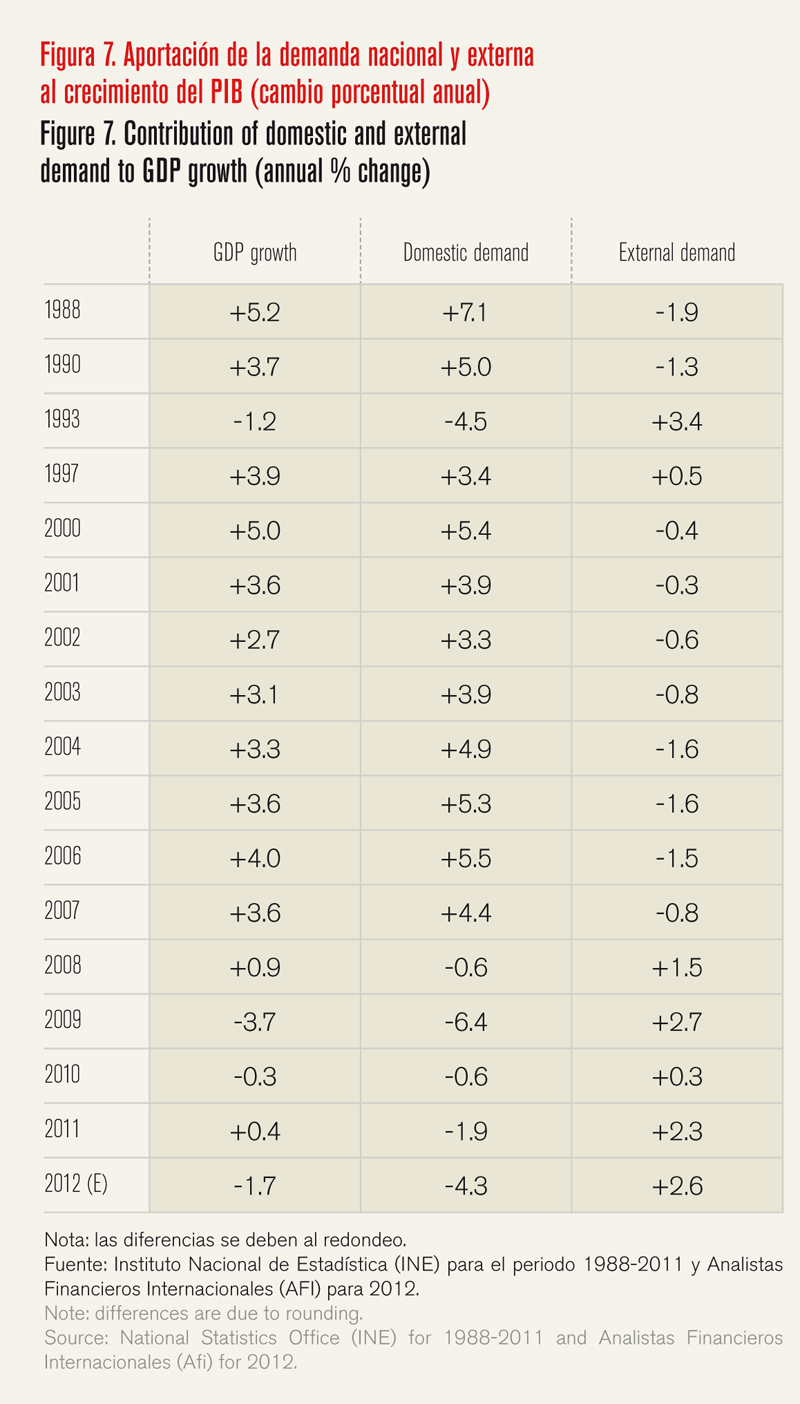

Spain’s structural problem is that external demand is only ever positive when the economy is in the doldrums, as figure 7 shows. Between 1988 and 2012, the contribution of external demand to GDP growth was positive in only seven years. Its largest contribution was in 1993, when Spain suffered its last recession, mild and short-lived compared to the current one.

But for the greater contribution to GDP growth of external demand, the recession, officially forecast to last until 2014, would have been deeper.

The comparison with 1993, however, is tenuous because until Spain joined the euro in 2002 it could resort to the policy option of devaluing its currency, the peseta, in order to restore or boost export competitiveness. This disappeared with entry into the euro and since then competitiveness can only be enhanced through internal devaluation, essentially by lowering wage costs and increasing productivity. The economy’s external competitiveness continued to improve n the first half of 2012. The competitive Trend Index, calculated on the basis of consumer price inflation as well as on the unit value of exports, registered gains.

Once the economy starts to expand again, external demand’s contribution becomes negative again. The challenge for Spain is to achieve a better balance between the different components of the economy in which exports play a greater and strategic role, like Germany. It is no accident that Germany has recovered more quickly than the other large euro zone countries as its economy is much more export-oriented and internationalised than Spain’s in good times and not just in bad ones.

This goes some way toward explaining why Germany’s seasonally-adjusted joblessness rate is less than 6%, one- quarter of Spain’s 25%. Germany’s rate, albeit cushioned by subsidies to companies to keep workers in employment while reducing their hours (a scheme known as kurzarbeit), is the lowest since records for a reunified Germany began in 1991, while Spain’s is the highest in 15 years. The comparison is even more stark in absolute terms: Germany, with a population of 82 million, has fewer than 3 million people out of work while Spain (population 47 million) officially has more than 5.7 million.

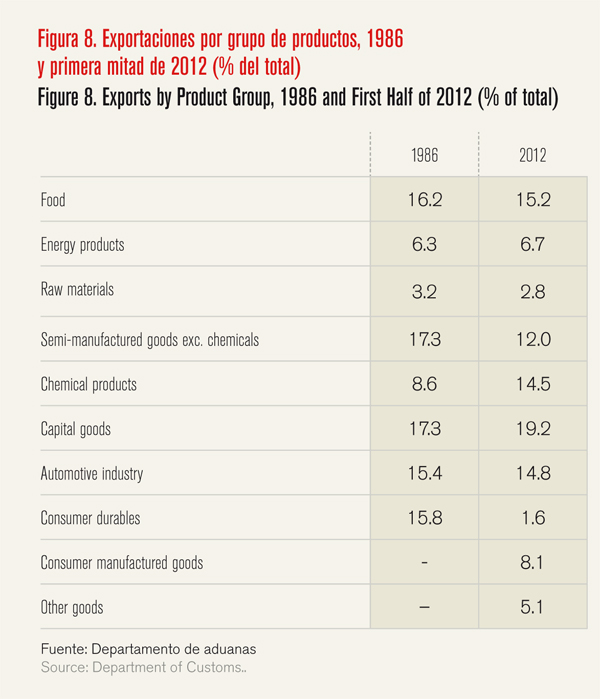

Traditionally an exporter of vegetables, fruit and wine, Spain today exports an increasingly diversified range of products (see figure 8), from oddities such as doughnuts (Panrico/Donut) to information and air traffic control systems (Indra) and space navigation equipment (GMV). Sectors with a high technological component, however, are under- represented in the structure of exports. In contrast, goods with an average technological component are relatively over-represented, and this is an area where competition is increasingly tough.

The geographical distribution of exports has also changed over the years. The EU 27 took 64.2% of Spain’s exports in the first half of 2012 compared with 52% in 1985, the year before Spain joined the then 10-member club. The proportion of exports that goes to the US has hardly changed at around 4%.

Institutional Presence

Institutionally, Spain is well represented abroad in the form of embassies, trade and tourism offices and branches of the Instituto cervantes (founded in 1991) for teaching Spanish and promoting the culture of Spanish-speaking nations. There are 118 embassies and 92 consulates, 100 offices of the Spanish Institute of foreign Trade (IceX) and more than 70 cervantes branches in over 40 countries.

The Rise of Spanish Multinationals

Spanish companies began to invest abroad in the 1960s, but it was not until the country joined the european community in 1986 and adopted the euro as its currency in 1999, which enabled companies to raise funds for their acquisitions at rates unimaginable just a few years back, that outward investment took off. eU membership changed the strategic focus of corporate Spain from one of defending the relatively mature home market –much more open to other eU countries– to aggressively expanding abroad. The liberalisation of the domestic market as european single market directives began to unfold made the big

Spanish companies, especially the state- run companies in oligopolistic sectors such as telecommunications (Telefónica), oil and natural gas (Repsol and Gas natural) and electricity (Endesa –Endesa has been more than 90% owned by Italy’s Enel since 2009) –all of which were to be privatised and become cash rich– and the big private sector banks, Santander and BBVA, conscious of the need to reposition themselves in the more competitive environment. The tougher environment was underscored by an inward fDI boom in the first years after eU entry when hardly a week passed without an acquisition and it seemed that Spain was up for sale.

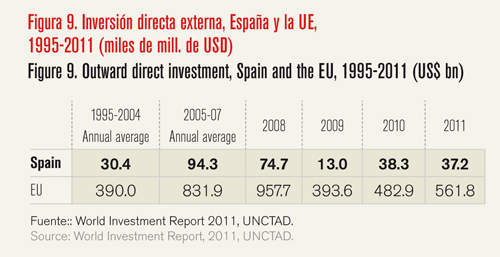

The strategic response to the threat of acquisition was to become bigger and go on the offensive. Liberalisation at home gave Spanish companies the opportunity to do this. And they seized it. Outward investment surged from an annual average of US$2.3 billion in 1985-95 to US$30.4 billion in 1995- 2004 and US$94.3 billion in 2005-07, according to UncTAD (see figure 9). In 1999 the stock of outward investment almost reached the level of inward investment and that same year Spain overtook the average developed country in the world in terms of its cumulative investments abroad.

Latin America was a natural first choice for Spanish companies wishing to invest abroad in a significant way. Between 1993 and 2000, during the first phase of significant investment abroad, Telefónica, Santander and BBVA, the oil and natural gas conglomerate Repsol, Gas natural, the power companies endesa, Iberdrola and Unión fenosa and some construction and infrastructure companies invested in the region. Latin America accounted for 61% of total net investment during this period –which averaged €13.1 billion a year excluding the Special Purpose entities (eTVes) whose sole purpose is to hold foreign equity–, compared with 22.5% by the eU-15 and 9% by the US and canada. Only the US, whose economy during that time was 12 times larger than Spain’s and in whose backyard Latin America lies, invested more.

As well as the companies’ own push factors, there were several pull factors. Two of them were purely economic: liberalisation and privatisation opened up sectors of the Latin American economy that were hitherto off limits, and there is an ongoing need for capital to develop the region’s generally poor infrastructure. Two are cultural: the first is the common language and the ease, therefore, with which management styles can be transferred. Another attraction is the sheer size of the Latin American market and its degree of underdevelopment. The macroeconomic fundamentals of Latin America as a whole and some countries in particular, such as Mexico and Brazil, had also become sounder as a result of major reforms, making the region a less risky place to invest.

Mexico, chile, Brazil and Peru have gradually achieved investment-grade status, which means the risk of debt default is minimal and institutional investors are less hesitant about investing in their financial markets. Lastly, democracy has been gradually taking root in an increasing number of countries.

The initial move into Latin America was, as Mauro Guillén has pointed out, the ‘path of least resistance’ for Spanish companies facing deregulation and take-over threats on their home ground (See his The Rise of Spanish Multinationals, cambridge University Press, 2005.). Spanish executives were ideally suited to handling new businesses in Latin America as they had gained a lot of experience of how to compete in industries under deregulation in their own country. By the early 2000s, Spanish companies had become among the largest operators in telecommunications, electricity, water and financial services throughout Latin America and the region a major contributor to the bottom line of a significant number of Spanish companies and banks.

While the 1980s were a ‘lost decade’ for Latin America, as countries struggled with foreign debt crises, the first decade of the 21st century has seen the continuation of a profound transformation that began in the 1990s and is benefiting Spanish investments in the region, though not without problems as the renationalisation in 2012 of the Argentine oil company YPf, acquired by Repsol in 1999 for €13 billion, dramatically showed. YPf accounted for more than a fifth of Repsol’s operating revenues in 2011.

Cristina Fernández, Argentina’s President, sent a bill to congress in April to put 51% of YPf in state hands. This followed the revoking of 16 petroleum concessions held by Repsol after it was accused of not investing enough and, as a result, increasing Argentina’s bill for imported energy. Repsol rejected the charges and took the case to international arbitration at the World Bank.

The shift away from Latin America as of the early 2000s, after Argentina’s financial meltdown, which hit Spanish banks and companies there but hardly affected the Spanish economy as whole, and into europe, particularly the UK, and the US and Asia, to a lesser extent, was marked by several emblematic investments – Santander’s €12.5 billion purchase of the UK bank Abbey in 2004, the acquisition by Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) of two small banks in california and Texas and Telefónica’s purchase in 2005 of a stake in china netcom and in 2006 its €26 billion acquisition of the O2 mobile telephony operator in the UK, Germany and Ireland–.

International expansion has greatly increased the size of Spanish companies. Spain had six companies in the fT Global 500 2012, compared with 273 US firms, 38 chinese, 40 British, 24 french and 19 German (see figure 10).

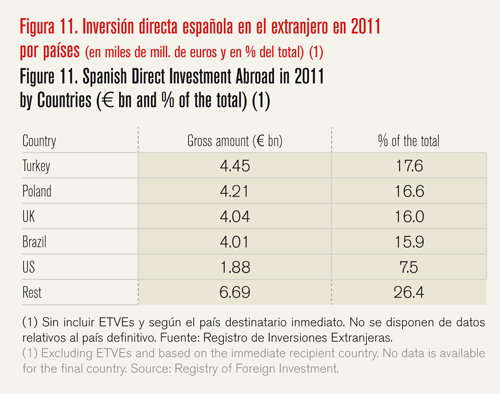

Gross Spanish investment abroad excluding eTVes (special purpose entities that hold the equity of companies located abroad for tax advantages) dropped 27% in 2011 to €11.2 billion. The main country receiving gross investment was Turkey, which is becoming an increasingly important trade partner for Spain and destiny of investment (see figure 11). Spanish investment in Turkey jumped from €232 million in 2010 to €4.4 billion. In 2011, the OHL-Dimentronic consortium won the tender for the €900 million contract to build a tunnel under the Boshporous and Técnicas Reunidas secured a €2.4 billion contract to modernise the refinery of Tüpras in Izmit, the largest ever awarded by the oil company and the seventh contract won by Técnicas Reunidas in Turkey.

A Glance at Some of the Multinationals

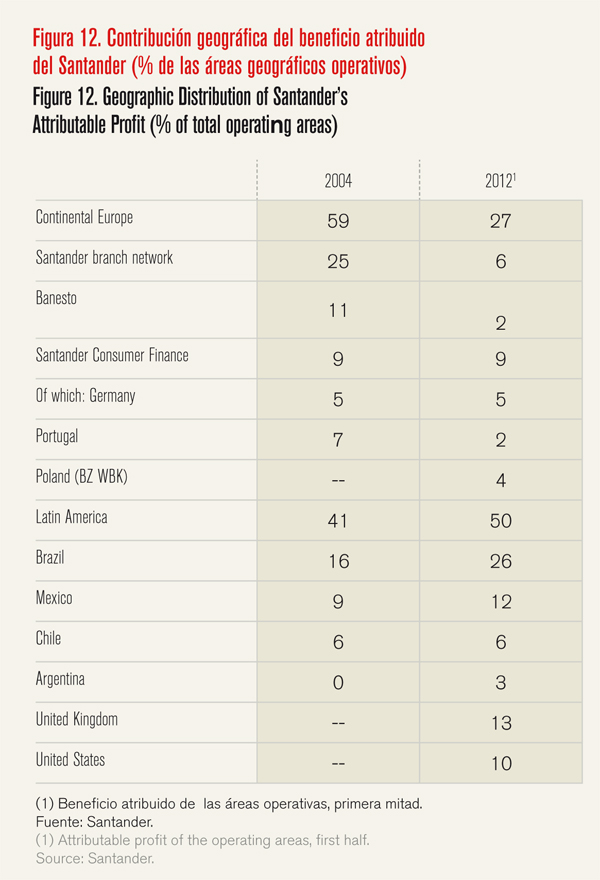

Santander’s rise from a local note-issuing bank founded in 1857 in the region of the same name to its position today as the euro area’s leading retail bank (and the largest by market capitalisation) with the biggest financial franchise in Latin America is a remarkable one. The product of the merger of three banks between 1991 and 1999, Santander operates in many european countries, including Germany, Portugal, Poland and the UK, where it owns Abbey, a leading mortgage bank, as well as in Latin America, with leadership positions in Brazil, Mexico, chile and Argentina, and in the northeast of the US (Sovereign). Santander’s reputation for aggressiveness and innovation started in 1989, when it was the first Spanish bank to offer remunerated current accounts. In 1985, Santander had 750,000 customers worldwide. Today, it has more than 102 million clients and 14,760 branches (more than any other international bank). Brazil generated 26% of the attributable recurring in the first half of 2012 compared to 14% in Spain (see figure 12). emerging markets accounted for 56% of profits.

Santander is the euro area’s largest bank by market capitalisation

BBVA was also founded in 1857 and is the result of the merger of three banks. It owns Bancomer, Mexico’s leading banking group, has the largest presence in the US among Spanish banks and was the first Spanish bank to break into china’s fast-growing financial sector in 2006, when it acquired 5% of CITIC Bank and a 15% stake in CITIC International financial Holdings, its Hong Kong-based offshoot. In the first half of 2012, Mexico provided 29% of the operating areas’ recurrent attributable profits compared to 19% generated in Spain. emerging markets contributed 57% of gross income.

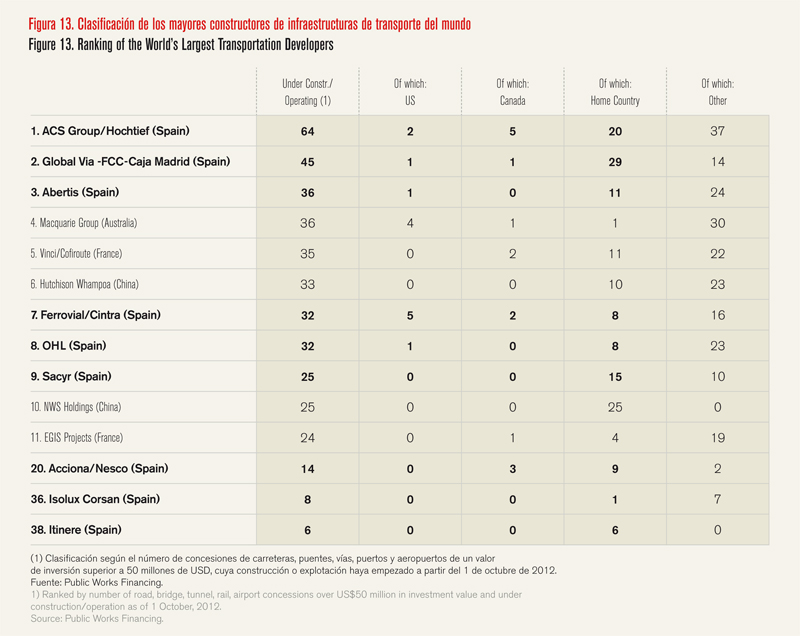

In renewable energy, Spain has three companies –Acciona, Gamesa and Iberdrola– that are leaders in their fields. Acciona is the biggest developer of wind farms, Gamesa the fourth-largest manufacturer of wind turbines and Iberdrola, the largest Spanish electricity company, the world’s biggest wind- power operator. In the building and management of transport infrastructure, Spain leads the world with six companies in the top 10 (see figure 13).

Perhaps the most remarkable story of all is that of Inditex, the world’s largest fashion retailer by sales, whose sales quadrupled to €13.8 billion between its initial public offering in 2001 and 2011. The number of its stores, with eight sales formats, the best known of which is Zara, rose from just under 1,000 in 1997 in fewer than 20 countries, when the company was family owned, to 5,693 at the end of July 2012 (1,930 in Spain) in more than 80 countries. In 2011, 25% of sales came from Spain, 45% from the rest of europe and the other 30% from the rest of the world. Inditex opened 483 new stores in 2011, 130 of them in china for a total of 275. It plans to increase this number to 425 in 2012. Only Spain has more stores. Just over one-third of total sales in the first half of 2012 were outside of europe, compared to 29% in the same period of 2011.

Not all the multinationals are large companies. notable among the medium- sized ones are Freixenet, Miguel Torres, Osborne, CAF, Talgo, Mango, Europac, Pescanova and Viscofan.

Freixenet is the global leader of top quality sparkling wines

Freixenet became the leading global producer of top quality sparkling wines or cavas, based on the méthode traditionelle process, by the mid 1980s. Its iconic product is cordon negro in a frosted black glass bottle recognised all over the world. It produces some 200 million bottles a year (more than half of all Spanish sparkling wine production and 80% of exports) and has vineyards in California.

Miguel Torres, like freixenet based in catalonia and founded in the 19th century, is a leading wine producer, with vineyards in chile and california and not just in Spain.

Osborne, the producer of wines, spirits and pork products, dates back to 1772 and is one of Spain’s longest established companies.

CAF is an international leader in the design, manufacture, maintenance and supply of equipment and components for railway systems. for example, it worked on the Heathrow express in the UK, the Hong Kong airport rail link and in Turkey won contracts for the high-speed train between Istanbul and Ankara.

Talgo is also in the railway business. It began in the 1920s when a Basque railway engineer, Alejandro Goicoechea, pioneered a new method for building railway cars, which minimised their weight by using lighter materials and reducing the cars’ height, thereby enabling them to make turns at relatively high speeds, and introduced other novelties including a different form of suspension. In 1974 the Talgo became the first high-speed sleeper train in the world (covering the Barcelona- Paris route). Today, it has routes in the United States, Argentina and Kazakhstan.

Mango is a clothing retailer with more than 2,000 stores in over 100 countries.

europac is a leader in the packaging sector, with plants in Spain, france and Portugal.

Pescanova is one of the world’s top-10 fishing companies with a fleet of 120 vessels.

Viscofan is the global leader in the production, manufacture and marketing of artificial casings and wraps for the meat industry.

Conclusion: The Need to Promote the Spain Brand

Spain has come a long way in the last 30 years, but the image of the country (and

hence of its companies), albeit severely tarnished by its profound economic crisis, is out of sync with reality. Governments so far have been loath to get involved in the country brand issue.

In 2003, the Elcano Royal Institute, the Madrid-based think-tank, the Association of communication Managers (Dircom), the Spanish Institute for foreign Trade (IceX) and the Leading Brands of Spain forum (fMRe) published a report putting forward proposals for strategies to improve and manage Spain’s perception and image abroad. The main conclusion was that as a nation brand is a matter of state, beyond party or ideological differences because it affects everyone, it needed to be centrally coordinated with the involvement of both the public and private sectors. Since then very little has been done to implement the recommendations. Promoting the Spain brand does not sit well with all of Spain’s 17 autonomous regions, particularly catalonia and the Basque country, the most nationalistic. These and other regional governments prefer to promote their own image and brands instead of going under a Spain wide umbrella.

José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the former Socialist Prime Minister (2004-11), recognised the need to do something when he announced in June 2008, flanked by Kofi Annan, the former Un Secretary General, that a public diplomacy commission would start to operate in 2009, but nothing was done to set it up. The governments of Germany, finland and the UK, for example, have successfully enhanced the image of their countries through such commissions and re-branding initiatives.

The country brand concept requires a bipartisan approach. In the increasingly globalised world, in which price is not always the overriding factor, a brand, an intangible asset, is more and more the way companies and countries compete. The better known a country’s brand, which incorporates many elements including its products, companies, culture, sports and international cooperation, the easier it is for a country and companies to enjoy success, particularly among first- time buyers, as this hinges, to a varying degree, on the prior image consumers have of the nation that produces them.

A good example of co-operation is the alliance between the private and public sectors in the Leading Brands of Spain forum, which approved a brand and image plan in 2008. The forum’s more than 100 companies generate over 40% of Spain’s GDP. The conservative government of Mariano Rajoy, which took office at the end of 2011, is actively supporting and fostering the Spain brand and hence that of companies. José Manuel García-Margallo, the foreign Minister, is making foreign policy more commercially focused. Given the depressed state of the Spanish economy, this overdue initiative makes a lot of sense. The government has also created the post of High commissioner for the Spain Brand with the rank of secretary of state, which is held by Carlos Espinosa de Monteros, an experienced businessman.

Spain’s process of internationalisation has been very positive so far, except for upsets like Argentina’s nationalisation in April 2012 of YPf, its biggest oil company, 51% owned by Repsol, and Bolivia’s seizure of Transportadora de electricidad, the subsidiary of Red electrica, the Spanish electricity grid. The collapse of the construction sector as of 2008 brutally exposed the shortcomings of Spain’s lopsided economic model, which is excessively based on bricks and mortar and tourism. The economy needs to become more internationalised through exports and direct investment abroad in order to create jobs on a more sustainable basis and of higher quality.

WILLIAM CHISLETT. A former Financial Times correspondent and author of three books on Spain for the Elcano Royal Institute, of which he is an associate researcher. He is a member of the Committee of Ambassador Brands and Spain Image of the Leading Brands of Spain Forum. His book on Spain will be published by Oxford University Press in 2013. www.williamchislett.com