Introduction

In the global economy there are different growth models. Some countries, like the US, UK and Spain, are used to growth on account of strong domestic demand backed by economic policies that encourage lending, investment and consumption. Other models, such as those of Japan, china and Germany, rely more heavily on the foreign sector, thus exhibiting significant current account surpluses, which mean that they are financing other countries with their savings.

However, one model is not inherently better than the other as there are several ways to have a successful economy. It is precisely the diversity of voters’ preferences that determines how some models have one particular direction or another.

However, in times of economic crisis and low growth, such as those currently experienced by Spain and the majority of advanced economies, it is clear that countries with a dynamic foreign sector and with competitive, international companies as well as foreign surpluses have a clear advantage as there is no ongoing need for external financing in times of credit shortages. This is because the global economy continues to have significant growth poles (particularly in emerging economies), so foreign demand appears to be the key to generating growth and employment in a context where domestic demand has collapsed owing to high debt levels, bottlenecks experienced by the financial sector and the procyclical cuts that many countries are forced to implement in exchange for external financial support.

Above and beyond the advantages that export-oriented countries have to overcome the difficulties, it is also true that even the countries that rely more on domestic demand have a great deal to gain if they manage to go global with their companies. While it is true that not all countries may become net exporters (for this to occur the world would have to trade, and have a surplus, with other planets), there is significant room for manoeuvre for countries to improve their exports. In fact, when a country internationalises its economy, it tends to increase both its imports and exports, while simultaneously increasing its foreign investments and productive capital inflows. And this dynamic, which is a win-win situation, stimulates the growth of all countries involved in the process, not just those that export more and invest more abroad.

That is why, beyond the fact that in the current recession experienced by Spain exportation seems the best recipe for growth in the short term, it is also advisable to make the most out of this necessity and to use the crisis to transform part of the Spanish manufacturing structure so that, in the future, it may have a pattern of more solid, stable growth. And this significantly enhances the foreign sector and the internationalisation of companies.

As we will illustrate in the following pages, Spanish companies are well equipped to compete in international markets. In fact, Spain has first-class multinational companies in multiple sectors, Spanish exports have had the highest growth in the euro area since the start of the crisis and the market share of Spanish companies in world markets has remained stable when that of the most advanced countries has fallen owing to increased competition from emerging countries. However, only a few Spanish companies export, both because their average size is too small to allow them to conquer foreign markets and because they were so used to strong domestic demand there was never any need for them to go global. Therefore, the challenge is to make more companies export.

Spain also faces challenges in the field of international investment. The most important thing is to remain an attractive destination for foreign companies in a context of increased competition and a weak domestic market in which transnational value chains are increasingly important and determine, in turn, the role of each country in trade flows. So Spain has to offer more than just low wages, political stability and legal certainty (its ways of attracting capital in the eighties and nineties). It has to change its model of international integration.

These are the issues addressed in this paper. first, we will analyse from a theoretical and general point of view the benefits of the internationalisation of the economy. Then we will analyse the profile that internationalisation has had in Spain, with special emphasis on the weaknesses of the model of international integration in recent decades. finally, lessons and recommendations are presented on the basis of both international and Spanish empirical evidence.

The advantages of internationalisation

At a macroeconomic level, there is no conclusive empirical evidence showing that more open economies reach higher levels of income and welfare. This is because the determinants of economic growth are basically all internal factors (good institutions, accumulation of physical and human capital, macroeconomic stability, etc.) [ In fact, although there is a correlation between trade openness and income level, it is not clear that the first factor explains the second. In addition, rapid and disorderly financial openness has proved counterproductive for many developing countries because it can lead to financial crises ]. However, it has been proven that in the long term, a gradual and orderly openness to trade, combined with other factors favours development, as well as the fact that direct investments accelerate growth when they transfer technology to the host country, they pay their taxes and create jobs, that is, when there are no enclaves isolated from the rest of the domestic economy, which tends to occur in primary sectors and in countries with weak governance. Beyond these ambiguous, macroeconomic results, recent studies of businesses clearly confirm the advantages for a country of having highly international companies. furthermore, it is clear that the high level of current economic interdependence offers many more opportunities or niches for growth for outward-oriented companies than those that existed pre-globalisation in the fifties or sixties of the twentieth century. And, as mentioned above, these opportunities are particularly interesting for countries like Spain, where domestic demand has collapsed.

What does internationalisation add?

In recent years, academic research in international economics has begun to look at how the heterogeneity of companies within a country explains their different behaviour (Historically, trade models assumed that all firms in a sector were identical and merely explored the macroeconomic effects of the opening of economies to trade). The conclusions of these studies clearly show that most international companies have important advantages over non-international companies and that there are benefits for shareholders, employees and the country where it is located (whether it is the country of origin or of a subsidiary).

First, international companies are larger and produce more goods and services than those operating exclusively in the domestic market. Being bigger they can make better use of economies of scale and they have greater financial capacity, which in turn allows them to invest more. They dedicate more resources to R&D, they are more innovative and are more used to operating in highly competitive markets, making them more efficient and achieving productivity levels that are significantly higher than those of non-international companies. Likewise, these companies also tend to create more jobs, attract more skilled workers by paying higher wages, have more and better training programmes for their employees, recycle their employees more effectively and have a global mindset for easy adaptation to new environments. They empower creativity and the development of their employees’ skills, making them more competitive in their domestic markets.

Therefore, exporting and international companies better resist economic downturns, both in terms of production and employment. Having higher levels of productivity and the ability to diversify their risks, offsetting falling sales in one market with higher sales in others, they have a much lower “mortality rate” than companies that only operate in the domestic market (think about the case of Spanish companies in the current macroeconomic situation. The more international companies have survived thanks to exportations).

Finally, international activity generates a large number of positive externalities both for the companies and the country as a whole (what is known in economics as spillover). Thus, the technological innovations that these companies produce tend to infiltrate (sometimes slowly due to the protection afforded by patents) into other sectors, fuelling demand for other companies to which they outsource intermediate inputs and, in general, paying more taxes than smaller and less outward-oriented companies.

In terms of commercial internationalisation (exports) there are virtually no, drawbacks, however assessing openness to international investment flows is a bit more controversial. When considering the impact of international capital flows, economists use a medical analogy and speak of good cholesterol (fDI) versus bad cholesterol (portfolio investment, sometimes called hot money). In principle, there is consensus that fDI inflows are essentially good for the growth of the receiving country, while the inflow of portfolio investment can be risky because the hot money is susceptible to panic and being suddenly pulled out from a country owing to destabilising events, which can lead to financial crises. Still, as the phenomenon of fDI is closely linked to industrial relocation and the outsourcing of services, its advantages are sometimes open to debate.

Spain, where abuse by foreign companies is uncommon, there is consensus on its benefits for the economy. The fDI transfers technology and know-how, creates jobs, attracts talent and physically contributes to sustainable public accounts. In the case of the fDI that a country makes abroad, although relocation will generate a loss of domestic jobs, many of these jobs can be offset by new (but different) jobs that are created domestically as a result of the expanding sales of the company upon extending its field of activity to new international markets. In fact, both theoretical models and empirical evidence show that the internationalisation of developed economies is associated in the long term with creating highly-skilled jobs and high productivity, which more than compensates for the job losses that result from the phenomena of relocation and outsourcing (AfI 2010, Kohler and Wrona 2010). furthermore, as (AfI, 2010: 18) illustrates, companies follow a more multi-location model than a relocation model, allowing them to create more jobs in most cases. Still, it should be noted that some relocations are net job destroyers, although it also should be highlighted that these jobs may not be sustainable in the long term in the local market once the countries have opened up to international trade. Thus, sometimes the relocation of a part of production is the only option so that the company does not disappear.

Companies follow a more multi-location model than a relocation model, allowing them to create more jobs

A look at the commercial and financial internationalisation of the Spanish economy

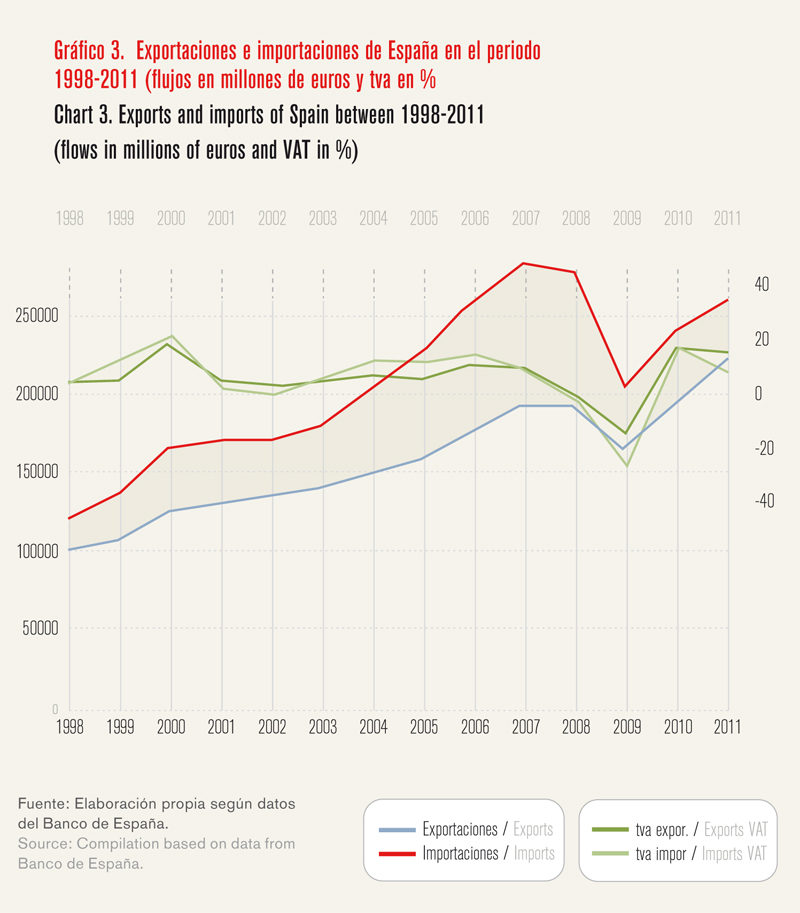

The Spanish economy has taken, in the last decade, a major step in its degree of internationalisation. The trade openness rate (exports plus imports over GDP), standing at the beginning of the 2000s at around 40%, has exceeded 60% in 2012. While it is still below the level reached by Italy (72%), france and the UK (75%), it exceeds that of the U.S. (30%) and Japan (40%). The growing internationalisation of current transactions has been accompanied by the full freedom of capital movement, meaning that the internationalisation of the Spanish economy has also intensified in the area of investments.

Thus, in late 2011 Spain had a larger stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) than that registered for foreign direct investment in Spain. The stock of Spanish portfolio investments accounted for just over 25% of foreign portfolio investment in Spain and the stock of other Spanish investment abroad was 50% of that accumulated for other foreign investments in Spain. The Spanish economy has been at the forefront of an intense integration process in the global economy mainly owing to its inclusion in the euro zone. However, the dynamics of its growth model have led, unfortunately, to an unbalanced external integration. The new funding opportunities that the creation of the euro opened up intensified capital inflows which generated the growth of non-tradable sectors (especially real estate) that, in the end, have proven to be counterproductive.

As a result, this financial integration has encouraged significant changes in the competitive conditions of companies, causing an intense and ongoing imbalance of the current account. The financial crisis in which we find ourselves has highlighted the urgent need for change in the form of international integration. It is necessary to promote exports of both goods and services and to attract new foreign direct investment to increase the participation of our activities in global value chains.

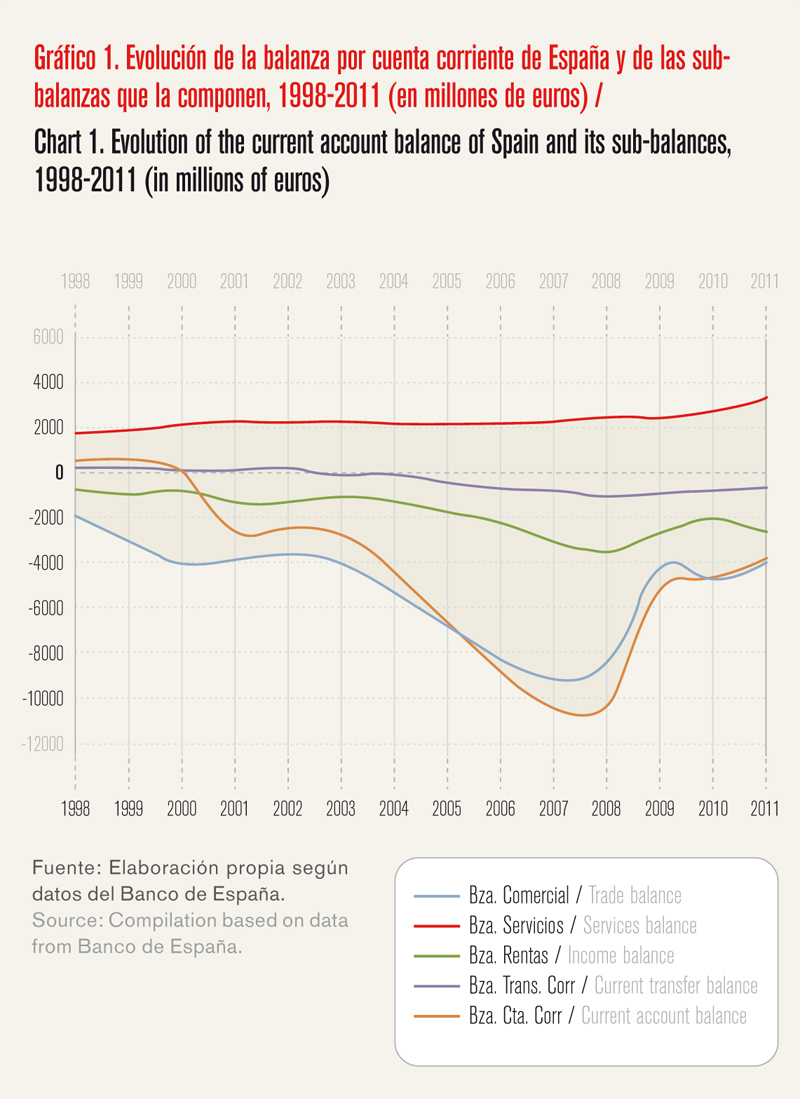

To date, the external imbalance (reflected in the current account deficit) is mainly attributable to oil imports, which still accounted for 86% of the trade deficit in 2011 (Bonet, 2012). And it is also owing to the deficit in the balance of payments and current transfers (see chart 1). Only the service trade balance, with a high prevalence of tourism, helps to reduce the current account deficit, but its insufficient diversification to other services, including knowledge intensive services, does not offset the balance of goods deficit.

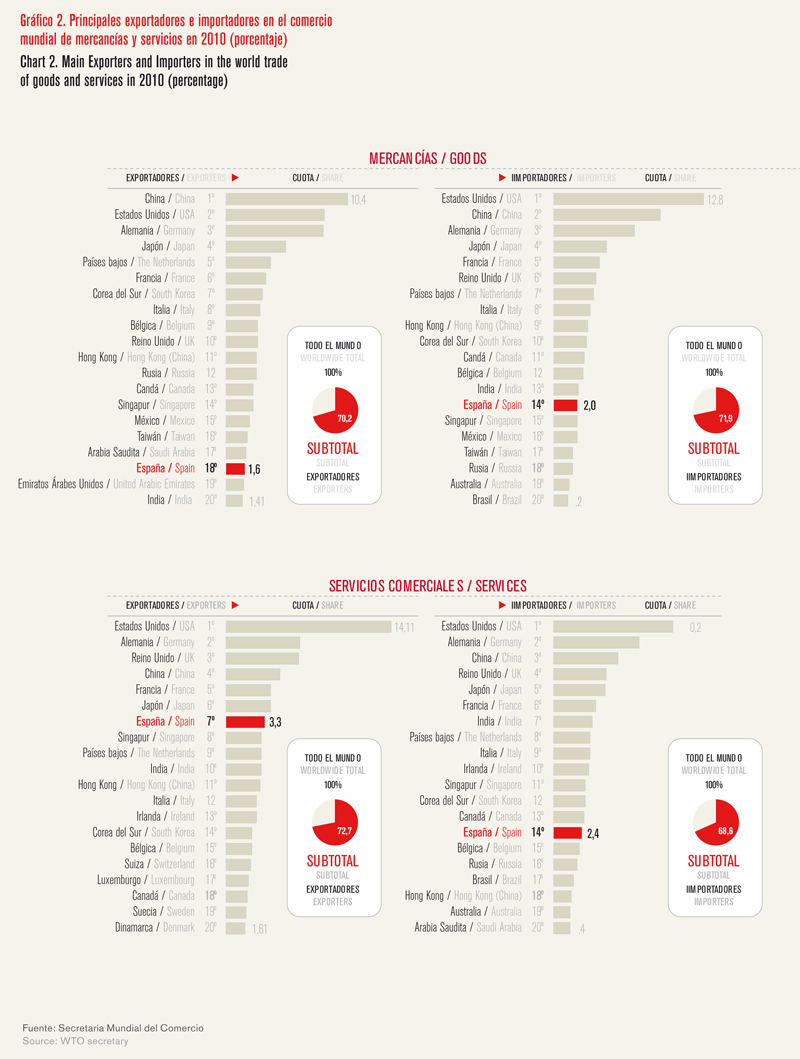

Nevertheless, exports of goods performed well since joining the euro until the crisis in 2008 and, after a sharp drop in 2009; they have exceeded the pre-crisis level in both 2010 and 2011 with an outstanding cumulative growth rate of 30% (see chart 2). However, it is still surprising that exports of Spanish goods and services have retained their relative importance in world trade over the last decade and their share has remained at around 1.6% and 3.3% respectively up until 2010 (see chart 1). This indicates that Spanish exported products do not necessarily compete on price, but on quality, making them more resistant to competition from low-wage emerging countries.

The increase in exports was driven by the increase in foreign sales of exporters (intensive margin) and the growth in the number of companies that were launched for export to traditional markets and new destinations (extensive margin). The main export markets for goods are traditionally: the eU (66%), countries in Asia-Pacific (7.8%), Rest of europe (7.5%), Latin America (5.5%), Africa (5.4%) and the United States and canada (4%). The growth of exports to OecD countries is explained by an increase in the intensive margin, while in emerging countries like china, India, Russia, Morocco and Algeria this is explained by an increase in the extensive margin. An increase in exports from the combined perspective of markets and sectors is evident, about 95% of exports are characterised as “old products to old destinations” and only the remaining 5% consisted of “new products old destinations” (Bonet, 2012).

In 2009, when there was a sharp contraction of international trade as a result of the effect of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008, Spanish companies recorded a small drop in the markets where they were installed, which was key for the strong recovery of exports in 2010 and 2011 (see chart 2). Moreover, exporting companies that best adapted to the new external context were those with lower levels of debt (Gonzalez, Maria. J, et al. 2012).

Who have been the agents of the export process? In 2000, there were 66,278 companies in Spain; in 2007 this number had grown to 98,513 and in 2009 to 108,303. In 2007, there were 39,214 companies that had exported continuously for the last four years (Subdirectorate General of Analysis, Strategy and evaluation, 2009) and in 2009 this fell to 39,079 companies (AfI Report, 2010), only 135 less than in 2007 despite the sharp contraction in global exports in 2009.

The unfinished business is to increase the number of international companies

Although the number of exporting firms may seem large in comparative terms with other european countries, exports are highly concentrated. A group of about 475 large companies, which exported more than 50 million euros and represented 0.5% of total export companies, were responsible for, up until 2009, 56% of the total export volume. This would seem to imply that in Spain few companies still export, so the unfinished business of the Spanish economy is to increase the number of international companies. This requires increasing the size of the average Spanish company, which is significantly smaller than that of other countries where a larger number of companies export, such as Germany.

From the perspective of a strategy to strengthen export capacity and to increase participation in global production chains, it is relevant to point out that “about 40% of total Spanish foreign sales are made by foreign companies established in Spain” (AfI Report, 2010:79) and that foreign capital presence in the Spanish production framework has increased shareholding in the capital of companies that export regularly and less shareholding in inward- oriented companies (AfI Report, 2010:79).

Financial integration of the Spanish economy In the 1990s, there came a growing financial integration that significantly intensified in the 2000s. The traditional importance of inflows of foreign direct investment was accompanied by a remarkable outflow of foreign direct investment from Spanish companies. In 1997, the Spanish economy became a net direct investor as outflows exceeded, in most years, inflows. In 2011, the Spanish fDI stock abroad accounted for 47% of GDP and the fDI stock in Spain stood at 43%, reflecting the significant progress in the path of international investment by Spanish companies in the last fifteen years. The next section pinpoints the main features of this important process.

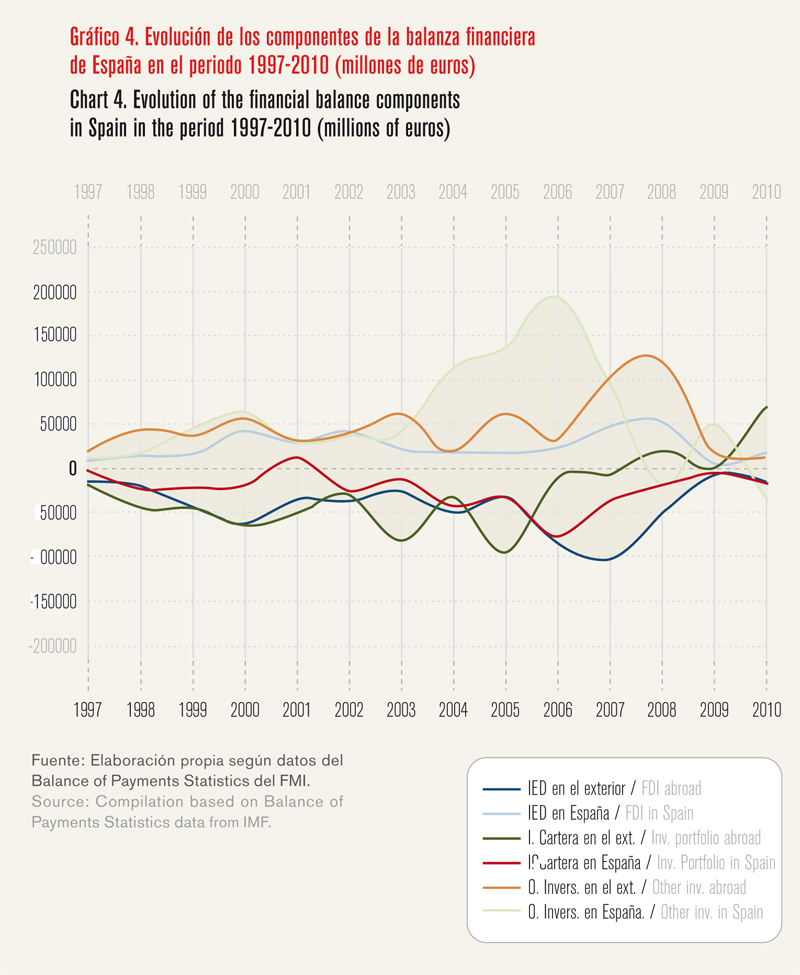

The increasing financial integration also highlights the intensity of portfolio investments and other investments made and received especially in the 2000s until the beginning of the financial crisis in the summer of 2007 (see chart 3). Since then there has been a sharp reduction in portfolio investments and both foreign investment in Spain and Spanish investment abroad.

In particular, as Merler and Pisani-ferry (2012) explained, since the european interbank market began to fragment and risk premiums in Spain and Italy began to rise (in late July and August 2011, in December of the same year and at various times in 2012), the Spanish economy has been experiencing a sudden stop process.3 Private flows that have traditionally financed the current account balance have been withdrawn by the contagion of the Greek crisis and the risk of redenomination that would result from the break up of the euro, being replaced by public funding from the eurosystem. This buffer, which has provided the necessary resources to offset the lack of liquidity in the interbank market in the euro area, has meant that Spain accumulates liabilities vis à-vis the eurosystem, which are recorded in the TARGeT2 system. However, it would be desirable to standardise financial flows and for private capital to flow back to the south. However this requires changes in the governance of the euro and ecB action to end rumours of a possible break up of the single currency.

FDI of Spanish companies abroad

Spanish companies began a process of rapid expansion abroad in 1990, directing nearly 65% of investment flows to Latin American countries. This internationalisation process continued in the 2000s, the decade in which Spanish companies ventured beyond Latin America, in particular the eU (see chart 4).

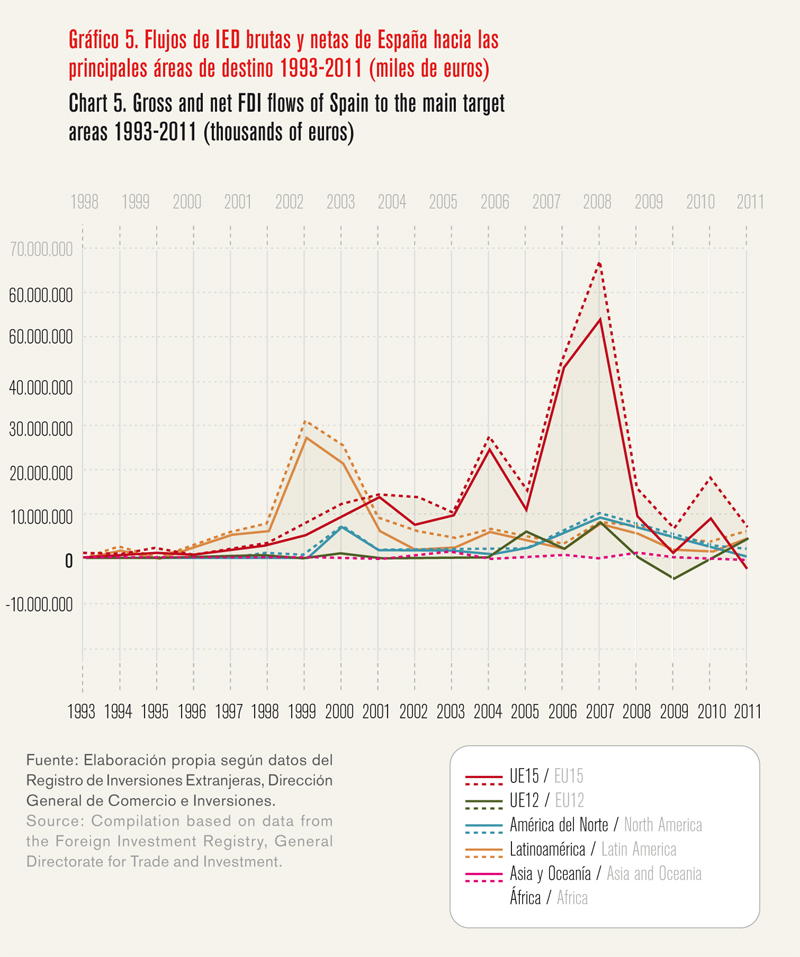

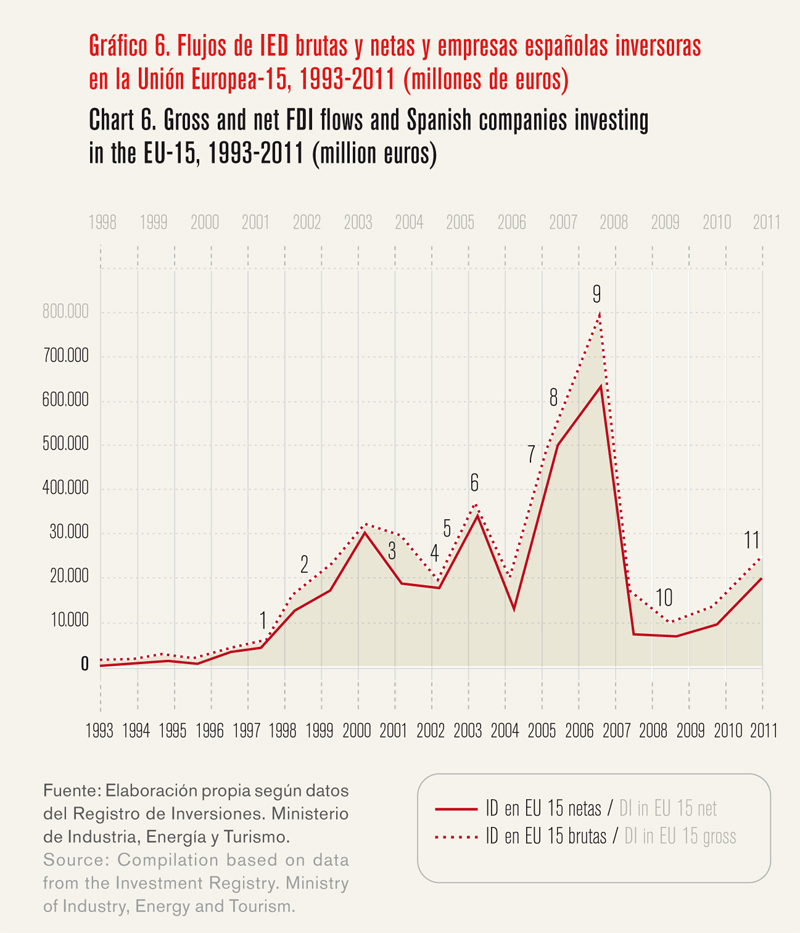

In the eU-15, the Spanish fDI went to two groups of countries: a) the first, which absorbed 92% of flows consisted of the United Kingdom (46%), the netherlands (21%), france (10%), Italy (6%), Portugal (5%), Germany (4%), b) the second, which attracted 8%, consisted of: Belgium (2%), Luxembourg (1.5%), Austria (1.5%), Greece (1%), Ireland (1%), Sweden, Denmark and finland. The new trend towards european Union-15 countries was the result of investments in large companies (see chart 5) that carried out outstanding acquisition operations, especially in the first group of countries of the area.

In the decade of the 2000s, the number of companies with investments abroad increased, so that by the end of 2008 there were already 2000 (OeMe, 2010: 91), representing 2.4% of the total Mncs and positioning the Spanish economy in the 12th spot worldwide in terms of the number of international companies. As happened with exports of goods and services, Spanish fDI abroad had been achieved by only a handful of companies. The largest presence abroad is held by 24 business groups that have a presence in over 30 countries (OeMe, 2010: 106-107). They are followed by 62 companies with a presence in between 10 and 19 countries then 174 business groups with operations in between 5 and 9 countries, and finally, a large group of 1192 companies with presence in between 1 and 4 countries (Arahuetes, 2011).

The 2.000 companies with international investment had 5349 companies abroad, in the categories of subsidiaries and/or affiliated companies located in 128 countries. Some 41.4% of these companies were in the european Union-15 (OeMe, 2010, p.107), which ranks the european Union-15 as a prime Spanish investment destination in terms of flows, stock and number of portfolio companies. countries in the european Union-12 were the fourth recipients of Spanish investments, and include Hungary, the czech Republic, Poland and Romania (OeMe, 2010).

The second investment destination of Spanish companies was Latin America and focuses on three groups of countries: a) the first, which absorbed 88% of the flows, was formed by Mexico (35%), Brazil (33%), chile (11%) and Argentina (8%), b) the second, which attracted 10.5% of flows consisted of Uruguay, Peru, colombia, Venezuela, ecuador and the Dominican Republic, c) and the third, with 1.5% of the remaining flows, was composed of Panama, costa Rica, Guatemala and el Salvador, and, to a lesser extent cuba, Bolivia, Honduras and Paraguay (see chart 6).

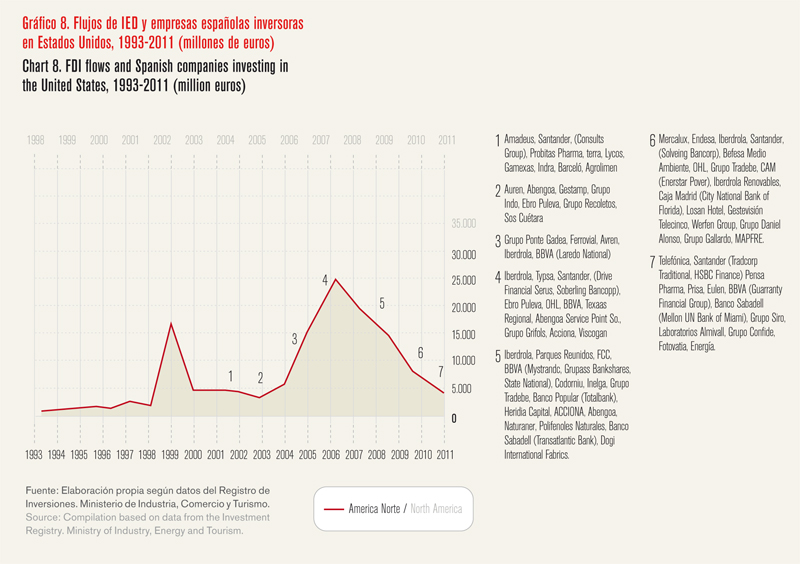

In the 2000s, the United States has become a market with an increased capacity to attract Spanish investment. This country accounted for 6.9% of the 5349 Spanish companies abroad –subsidiaries and/or affiliated companies–, until 2008 (OeMe, 2010, p.107), and was ranked as the third investment destination for Spanish companies in terms of flows, stock and number of affiliated companies (see chart 7).

Direct investment by foreign companies in Spain Another relevant dimension of the internationalisation of an economy that plays a crucial role in the shaping and transformation of the productive structure, job creation and the performance of the external sector consists of direct investments from foreign companies. fDI in Spain is key in the strategy to overcome the crisis with productive, technological and competitive force.

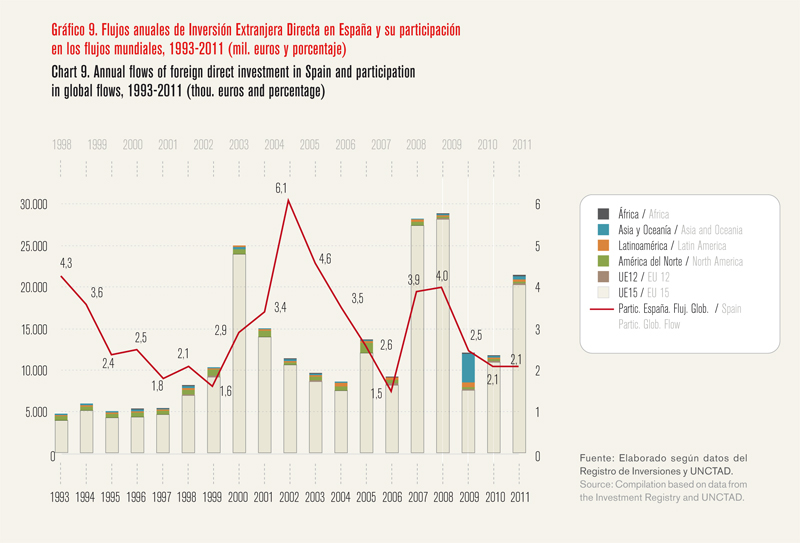

The Spanish economy has a deep-rooted tradition in its ability to attract foreign direct investment since the onset of modernisation in the 1960s. This ability was retained even in the early 2000s, despite the attractiveness of the economies of central and eastern european countries that were incorporated into the eU. In this sense, annual flows received went from 2.9% of global fDI flows in 2000 to 3.9% in 2004. In the following years, the flows were recovered in absolute terms while share in global volume in 2007 and 2008 increased (see chart 8). even in the worst years following the 2008 crisis, the Spanish economy reduced (but did not lose) its appeal as an investment destination, receiving 2.5%, 2.1% and 2.1% of global investment in 2009, 2010 and 2011 respectively (see chart 8).

Regardless, more fDI must be attracted to continue the modernisation of the productive structure of the economy and for the necessary growth of exports and for job creation. To this end, the attraction of new fDI projects requires the adaptation of the comparative advantages of the Spanish economy to the new productivity requirements of the highly competitive environment that globalisation demands in times like these. The countries that maintain their ability to attract direct investments are experiencing the highest growth rates (Delgado, Ketels, Porter and Stern, 2012).

In this respect, policies must be adopted that enable Spain to regain the level of appeal it had in earlier times for fDI and that it maintained until 2003.

IV. Lessons for the future

The european monetary union was built on the idea that, with the disappearance of exchange rate risk, external imbalances between member countries could be financed in the international financial markets by limiting the risk arising from the economic players in the countries. financial transactions between the countries in a monetary union do not have any special characteristic differentiating them from transactions between regions within the same country. This vision was the most widespread and well accepted and was thus detailed by the european commission in its report One Market, One Money (1990) when it noted that upon the disappearance of a restriction of balance of payments in a eMU, “private markets will finance all viable borrowers, and savings and investment balances will no longer be constraints at the national level” (Merler and Pisani-ferry, 2012:2).

FDI in Spain is one of the keys to overcoming the crisis

According to this view, it was unthinkable that countries could suffer financial crises resulting from the excessive external indebtedness of their private economic agents. Let alone was it thinkable that a country would be able to register a sharp deterioration in its financial system which would require special assistance programmes and strong support from the states. And even less thinkable, if this is possible, was the possibility that the financial situation of companies and households, along with a prolonged economic stagnation, could finally unleash a contagion effect and compromise the sustainability of public debt.

It is true that the sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone was triggered by errors in the governance of the euro rather than by specific errors of Spanish economic policy, which in 2007 had a public surplus and a ratio of public debt to GDP below 35%. However, the crisis has shown that the Spanish economy has a huge external vulnerability due to its weak external sector and chronic imbalances in the balance of payments, which require ongoing external funding, which in turn gives rise to unsustainable private debt levels.

In this respect, perhaps the main lesson to learn from the crisis is that countries, even within a monetary union, should not neglect the supervision of the high domestic credit growth thanks to easy access to international finance, mainly from Union members, and the borrowing capacity of private agents. Due attention should be paid to the intense and prolonged expansion of imports (of consumer goods) and real estate booms when they coincide with large deficits in current account balances because these are unmistakable signs that countries are edging towards serious financial crises.

Several authors (Blanchard, 2007; Jaumotte and Sodsriwiboon, 2010; Giavazzi and Spaventa, 2010) already noted that the ongoing negative balances in the current account were a reflection of low levels of savings relative to investment volume, the credit boom owing to easy access to international financial markets (which fed the bubbles) and the sharp deterioration in competitiveness owing to the appreciation of real exchange rates. They also stressed that these processes could trigger abrupt adjustments that would lead to very long recessions owing to the inability to devalue the currency.

Because, unfortunately, Spain is in recession, it is important to inform public opinion of the urgent need for reforms to accelerate the deleveraging process and restore growth. This is important to guarantee the sustainability of public finances in the long term, to solve the problems of the financial system so that credit can flow again and to progress with structural reforms to diversify, strengthen and add value to the productive framework.

As in previous crises, exports and capital inflows in the form of foreign direct investment are essential. The former because they represent an indispensable addition for weak domestic demand and the latter because they allow the density of the productive framework to be increased and position Spain in global production chains, which will play an increasingly more important role. That is why the foreign sector is one of the keys to overcoming the crisis. not surprisingly, in Spain this sector is responsible for 6.5 million direct and indirect jobs; it has managed to increase the per capita income by $1,275 for each additional ten percentage points of opening rate and has the potential to create 25 jobs for every additional million euros of exports (AfI, 2010: 30).

This means that, apart from helping to redesign the euro, Spain’s main concern should be to address, as a priority, the challenges of the foreign sector. Otherwise, it will be doomed to low growth processes that make the sustainability of the welfare levels achieved difficult.

Bibliography

- Analistas financieros Internacionales (2010), Internacionalización, empleo y Modernización de la economía española, May.

- Arahuetes, A. (2011), “expansión global de las inversiones directas españolas”. estudios empresariales, no. 134, Deusto Business School.

- Blanchard, Olivier (2007), “current account deficits in rich countries”, IMf Staff Papers, Palgrave Macmillan Journals, vol. 54 (2), pp.191- 219, June.

- Bonet, Alfredo (2012), “Luces y sombras del sector exterior: la competitividad de las exportaciones españolas”, Presentación en el Real Instituto elcano, 25 April.

- Delgado, M., c. Ketels, M. Porter and S. Stern (2012), “The determinants of national competitiveness”, Working Paper 18249, nBeR, cambridge, MA.

- Dirección General de comercio e Inversiones (2010), flujos de Inversiones exteriores Directas 2010.

- Donoso, V. and V Martin (2008), “características y comportamiento de la empresa exportadora”, Papeles de economía española no. 115, pp. 170-85.

- Chislett, W. (2010), “The Way forward for the Spanish economy: More Internationalization” Working Paper 1/2010, Real Instituto Elcano.

- Ernst & Young (2012), Growth, Actually, european Attractiveness Survey.

- European commission (1990), “One market, one money: An evaluation of the potential benefits and costs of forming an economic and monetary union”, european economy no. 44, October.

- Madrid Juan, M (2009), “La empresa exportadora española. características y su papel en el crecimiento de las exportaciones en el periodo 2000-2007”, Boletin económico Ice, no. 2965, 16-31 May.

- Giavazzi, Francesco and Luigi Spaventa (2010), “Why the current account may matter in a monetary union”, cePR, Discussion Paper Series, December.

- González Sanz, M. J. and A. Rodríguez Caloca (2010), “Las características de las empresas españolas exportadoras de servicios no turísticos”, economic newsletter, november, Banco de España.

- González Sanz, M. J. and A. Rodríguez Caloca (2012), “Las características de las empresas españolas exportadoras de servicios no turísticos”, economic newsletter, november, Banco de España.

- Jaumotte, florence and Piyaporn Sodsriwiboon (2010), “current Account Imbalances in Southern euro Area”, IMf Working Paper, WP /10/139, June.

- Kohler, Wilhelm. and Jens Wrona (2012), “Offshoring Tasks, yet creating Jobs?,” University of Tubingen Working Papers in economics and finance, no 12.

- Merler, Silvia and Jean Pisani-ferry (2012), “Sudden Stops in the euro Area”, Bruegel policy contribution, no. 2012/06, March.

- Observatorio de la empresa Multinacional española (2010), La empresa Multinacional española ante un nuevo escenario Internacional, esade Business School and ICEX.

- Unctad, estadísticas Mundiales sobre Inversión extranjera Directa, consultadas en: unctadstat. unctad.org/TableViewer/tableView.aspx

- Unctad, (2012), World Investment Report. Towards a new generation of investment policies, United nations, Geneva.

ALFREDO ARAHUETES. Full Professor in the Economics and Business Science Department at Universidad Potificia de Comillas, Madrid, ICADE.

FEDERICO STEINBERG. Senior Analyst of International Economics at the Real Instituto Elcano and Lecturer in the Depart- ment of Economic Analysis at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.