We have entered a decade that will undoubtedly be that of the emerging markets. These economies have emerged as major catalysts for growth. now it seems they will become key players.

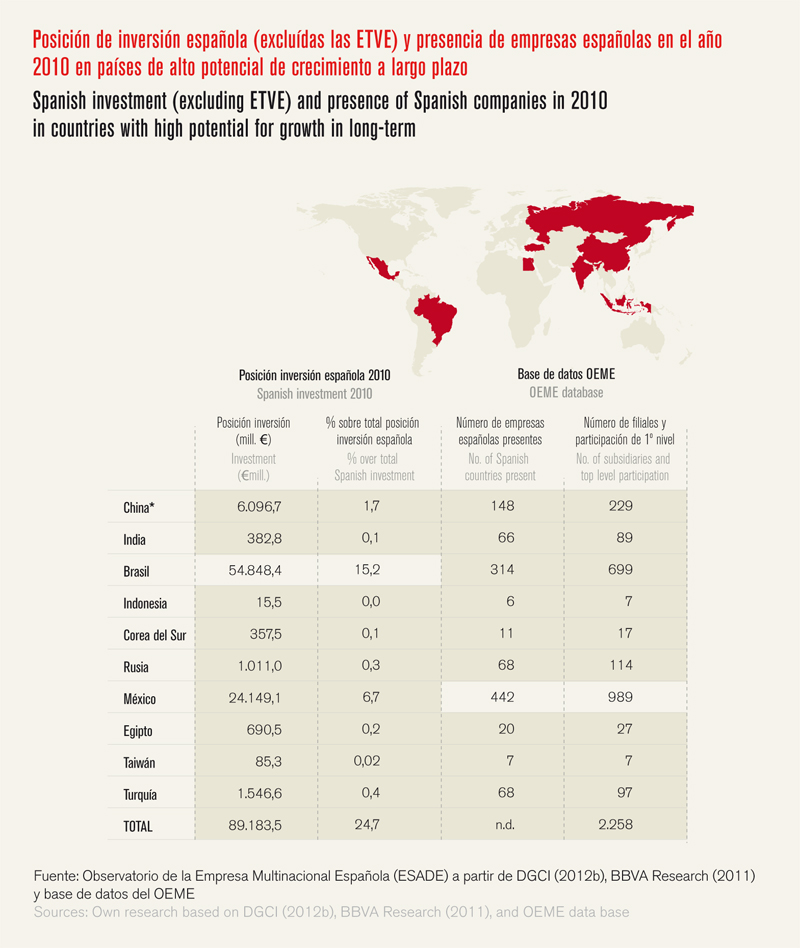

HSBC forecasts that by 2050 19 of the 30 largest economies in the world will be economies that today are classified as emerging (read the report). Overall, they will outweigh the current OECD countries. BBVA predicts that the group of countries called eagles (emerging and Growth- Leading economies) and nest countries (the next level of countries) will contribute over two thirds of global growth over the next ten years, while the seven most industrialised countries (G-7) will provide about 16% (read the BBVA’s report). The bulk of the growth will come from emerging Asia (60% of total growth between 2011 and 2020), ahead of Latin America (8%). The United States and europe will contribute just 20%. A country like Brazil will contribute twice as much to global growth in the next decade as Japan, Mexico more than Germany, colombia more than france, and Peru and chile more than Italy (read the report).

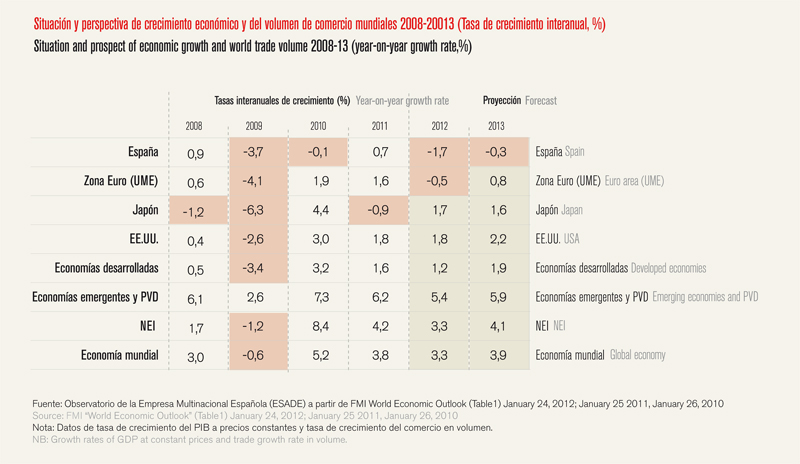

In other words, the major event of the beginning of this century is not the “global” crisis in OECD countries and in europe in particular. In fact, up until now, the crisis has not been “global” or “worldwide”. Interpreting it in this way is a mirage and makes us forget that from Peru to Indonesia, or from china to Brazil, many world economies have continued to grow. We have to reconfigure massively our mental eurocentric maps. The world of yesterday, focused on Europe and the US is no longer. The 2008-11 crisis is accelerating this world shift. Today, Brazil trades more with china, an emerging economy, than with any OECD country, the US, Germany, or Spain. This change is not only economic and financial: the wealth of nations is being reconfigured at a rapid pace as is innovation and technology.

The year 2012 confirmed the rebalancing of the world: while OECD countries were continuing to collapse, emerging countries continued their growth paths (albeit at a more moderate pace for many). A symbol of the great transformation we are experiencing is that china now stands ahead of Japan as the second largest world economy, while Brazil overtook Britain, after having done the same with Spain in 2010. Petrobras, one of the largest oil companies in the world, is a symbol of this Brazilian boom. It managed to break records with the largest public share offering in history worth 67 billion dollars. Overall, in 2011-12, emerging countries accounted for 40% of world GDP, 37% of total FDI and the bulk of global growth.

One of the drivers of this boom is undoubtedly the expansion of the middle classes in emerging economies. This dynamism is attracting more and more OECD multinationals. france’s Schneider electric, for example, already has more than 25,000 employees in china – the world’s second largest market after the United States and ahead of france. for many companies, the emerging markets now account for the bulk of their income, ahead of europe or the United States. In emerging Asia, the middle classes now represent 60% of the total population (1.9 billion people). In 2010, China, a country where 54 million people are already classified as high-income, became the leading market in terms of vehicle sales. The richest man in the world is no longer in the US but in Mexico (Carlos Slim, the owner of one of the most booming Latin America multinationals, América Móvil, which in 2012 just arrived in the netherlands and Austria). The reasons for the growing attraction of emerging economies are in the figures, high growth and the expanding middle classes, and all in an environment of lower borrowing, debt, deficit and with inflation under control.

Nevertheless there is another silent revolution that is taking place, another reason why companies from OECD countries also opt for emerging economies: not only will the 2010-20 decade be that of the emerging economies, because they are setting the pace of growth, but also because we will see increasing amounts of disruptive innovation from these countries. This will also change the profile of OECD multinationals. So two powerful movements will intersect: first we are witnessing the rise of emerging multinationals, even in cutting-edge sectors with high added value and strong technological components, and, on the other hand, we are seeing more and more innovation re-imported by OECD multinationals from emerging countries.

Emerging countries:

New global players The big news from the opening years of this new century is that emerging countries are no longer passive witnesses to world events. They have now become players and drivers in global change. Until recently, when we talked about the emerging countries, we Westerners did so with pity: they were “the Third World” or “developing countries”. Recent years have altered that vision and perception. now they are called ”emerging countries”. Semantics matters.

We have just crossed over the threshold of a new decade that will undoubtedly be the decade of the emerging markets. These economies have emerged as major catalysts for growth. now it seems they will become key players. The bulk of global growth comes from these countries, particularly from China, India, Brazil and Russia. What we are witnessing is an unprecedented shift of wealth from the nations that are rebalancing towards the emerging economies. The crisis in OECD countries is an additional factor accelerating this process.

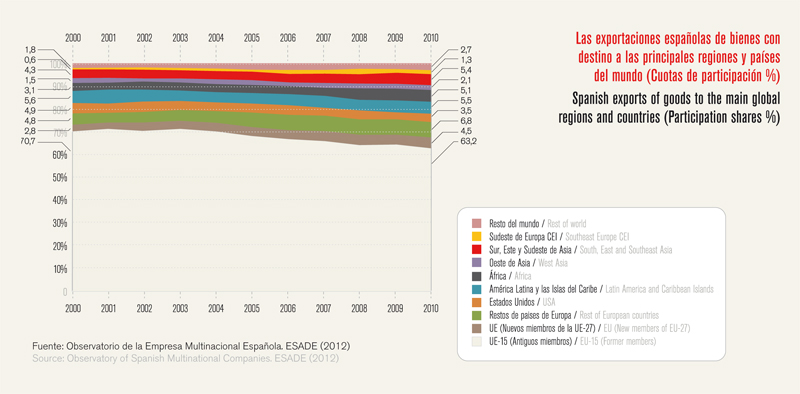

The world is been thrown off balance quickly: its focal point is no longer located in OECD countries. former notions of centre and periphery are now obsolete. Today emerging economies do more trade and investment among themselves than they do with OECD countries. The classifications of “developed” versus “developing” countries or even “OECD” and “emerging countries” are questionable. More and more emerging countries (Turkey, Korea, Mexico and more recently chile and Israel) are becoming OECD members today. The richest country in the world (Qatar) is not in the OECD, neither are some of the world’s most industrialised countries like Singapore or Taiwan. In 2011, for the first time, the export capacity of emerging countries exceeded that of the euro zone, despite German dynamism. Thus, the export capacity of emerging countries amounted to 26.6% of the global total, surpassing for the first time the total of the 17 countries in the euro area (25.9%). In 2012, this trend has been repeated.

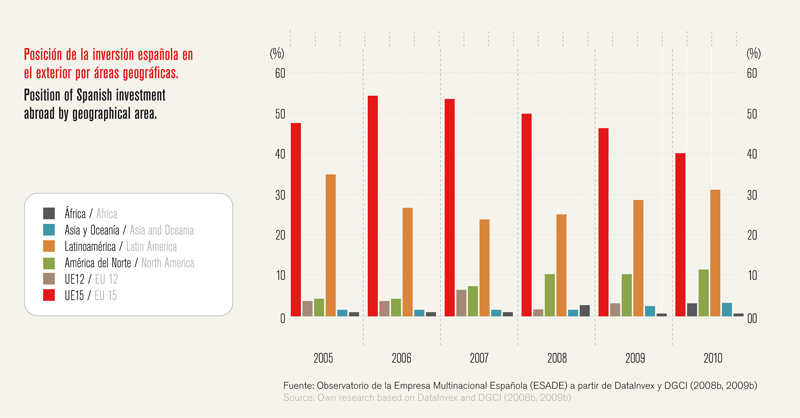

With the crisis in europe and the OECD countries from 2008-12, emerging markets, both in Asia and Latin America, have become the lifeline for revenues and the accounts of many firms in the Old continent, and particularly Spanish firms. In fact, the crisis is accelerating the international expansion of many companies. During 2012, over 60% of sales of Ibex 35 groups have come from abroad, beating national sales for the third consecutive year. Some groups, like Ebro foods, even generate more than 90% of their sales abroad. Others, such as Telefónica, BBVA, Santander, Repsol, Iberdrola, OHL, Gamesa and ferrovial, generate more than 50% of their revenues abroad. for these companies, much of their trade comes from Latin America. What over a decade ago appeared to be an uncertain, risky undertaking – often snubbed by international investors – has today become a great asset and move for all these companies. Latin America, has been, today is and will continue to be a great opportunity for Spanish groups.

The crisis is actually accelerating the process of internationalisation of the aforementioned groups, as well as Indra, Acciona and Abengoa, to name a few more. Latin America is now more than ever on the radar. In mid-2010, Telefónica acquired Brasilcel, taking full control of Brazilian mobile operator Vivo. Meanwhile, Banco Santander has also continued pushing hard for the region listing its Brazilian subsidiary on the stock exchange, while the OHL group did the same soon after, with its Mexican subsidiary. While Sacyr focused on Panamá, other engineering and construction groups also ventured into the continent. The Latin American subsidiaries have thus become the crown jewels of these groups. What’s more, these groups, through Latin America, have managed not only to maintain their revenues, saving their 2010-12 accounts, but the region, and Brazil in particular, has allowed them to raise capital and to attract global investors, particularly in other emerging markets. Thus, Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund has pumped around 2 billion euros into Santander’s Brazilian veins and soon the same will occur with Iberdrola, with similar quantities and for the same reason: its commitment to Brazil. Meanwhile, Repsol YPf also achieved an influx of capital from china’s Sinopec in its Brazilian subsidiary, managing to deleverage itself notably by selling 40% of its shares. Again, in this case, as above, Latin America became the magnet of interest from investors and global partners of Spanish multinationals.

Obviamente esta apuesta internacional no se limita a América Latina, aunque el resto de los emergentes de Europa del Este, Asia, África, y Asia siguen siendo las grandes apuestas pendientes de los grupos españoles. Como lo muestran las operaciones de inversiones en 2010-2012 de BBVA en Turquía, del Santander en Polonia, de las OPAs pendientes de ACS sobre la alemana Hotchief (para abrirse un hueco en Europa del Este) o de Ebro Foods sobre la australiana Ricegrowers (para hacerse un hueco en Asia), el imperativo de crecer fuera de las fronteras españolas sigue y seguirá fuerte. Por su parte Inditex ya está ahora en todos los continentes no sólo América Latina y Europa, sino también Asia (potenciando en particular China) e incluso África y Oriente Medio. Start ups como la gallega Blusens por su parte han hecho de Emiratos su base de expansión mundial.

Obviously, this international drive is not limited to Latin America. However, the rest of emerging countries in eastern europe, Asia, Africa, and Asia remain at the top of the pending operations list of Spanish groups. As shown by the investment operations of BBVA in 2010-12 in Turkey, Santander in Poland, the pending AcS takeover of German company Hotchief (to fill a gap in Eastern Europe) or the Ebro foods takeover of the Australian company Ricegrowers (to gain a foothold in Asia), the imperative to grow beyond the Spanish borders continues and will continue to become stronger and stronger. Meanwhile Inditex now has presence on every continent, not only in Latin America and europe, but also in Asia (particularly thriving in china) and even in Africa and the Middle east. Start- ups, like the Galician Blusens, have made the UAe their global expansion base.

Internationalisation towards the emerging countries in all regions has become an imperative. In fact, in 2012, the success of the High-Speed Railway in Mecca or the mega contract landed by Gas natural in India is obvious, to name a few landmark deals in emerging markets outside of Latin America. This region is presented as the main driver of the accounts of many of these groups. What was once – over a decade ago – an uncertain, risky bet has become a great achievement. concentrating efforts in emerging markets in other regions remains a pending task, above and beyond the ad hoc achievements of some multinationals in these countries. One of the blessings in disguise of the crisis in Spain is to convert the trend to expand into the emerging countries into a real necessity that is not just limited to America, but to all continents: Asia, Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, etc.

The current decade will be that of the emerging markets. not only because we will see the bulk of global growth concentrated in these countries, but also because there will be increasing amounts of frugal, disruptive innovation from these countries. There is no doubt that in this new decade the geography of innovation, as well as the wealth of nations, will also experience a massive rebalancing. What does the emergence of this new world entail for Europe? And what does this mean for Spain in particular?

Emerging countries: an opportunity for Spain?

As the crisis deepened in 2010-12, europe, and Spain with it, began to discount. Almost all of europe has a “sales” sign in the window. Industrial assets have plummeted and a lack of bank liquidity has transformed many businesses into perfect targets. The crisis has converted the european business landscape in a great hunting ground where prey abounds. This abundance has whetted the appetite of multinationals from emerging countries. The chinese have grasped this notion perfectly: in December 2011 the chinese sovereign wealth fund cIc was granted 50 billion more for acquisitions in europe, while, under the umbrella of its second sovereign fund SAfe, the government is structuring a new 300 billion dollar fund for acquisitions in the US and in Europe.

Thus chinese multinationals took control of the Swedish groups Volvo and Saab, picking up one after the other. At the end of 2011, china’s Three Gorges company pipped the German group eon to the post when it snatched up 21% of the capital of the Portuguese energy company eDP. With this share, the chinese not only became the main shareholder of the Portuguese group but also gained a toehold in europe (including Spain through Hidrocantábrico) and, in particular, in Brazil. The investment (almost 2.7 billion euros) is one of the most important ones ever made by a chinese group in europe. And this is only beginning: the electric company Ren, the Portuguese airline TAP, the oil company Galp, the public radio and television company (Rádio e Televisão de Portugal) or water company (Águas de Portugal) are some of the companies that the Portuguese State will have to sell. In Greece, Italy and many other countries, similar signs were hung.

The arrival of multinationals from emerging countries to europe does not however signal an end to the crisis. Before 2008, Indian groups, such as Mittal or Tata, for example, took control of iconic companies like Arcelor in france and Luxembourg or Jaguar in england. for more than a decade now, Mexico’s Cemex has been taking control of assets in Spain and england, snatching markets from france’s Lafarge and Switzerland’s Holcim. Such operations are not new. However, we are witnessing an acceleration of financial and industrial asset transfers in europe towards emerging economies. Put another way: the crisis is accelerating the rebalancing of the industrial and financial wealth of nations.

In Spain, the need for liquidity, or simply the search for (new) business partners, pointed many Ibex 35 groups in the direction of the emerging economies. They are no longer markets to be conquered or where to invest but also financial and industrial partners and sometimes, simply the new owners of the hunting reserve. Thus, in 2011 operations were multiplied: the Algerian company Sonatrach invested in Gas natural, buying almost 4% for the amount of 514 million euros; the Mexican group Pemex bought up a 9.5% stake in Repsol YPf; the Arab Qatar Holding fund purchased more than 6% of Iberdrola for a total of just over 2 billion euros (the previous year it had done the same with Santander, entering its Brazilian subsidiary with an investment of just under 2 billion euros for a total of 5% of the capital), the UAe’s IPIc ended 2011 by taking over cePSA in an operation that amounted to close to 4 billion euros. The Brazilian giant cSn, which attempted a purchasing operation in Spain in 2011 with the Gallardo group, is now interested in having a share in Repsol. Sacyr’s share in the oil company actually sparked many investors’ appetite for emerging countries. The Government of Beijing’s cIc sovereign fund along with the chinese oil company Sinopec were interested in having a stake in Repsol. At the end of 2010, Sinopec and Repsol joined forces to operate in Brazil in an operation that involved a capital gain for Repsol of 3.7 billion dollars.

Emerging markets from Brazil to India including china and the Middle east have been transformed over the past decade into investment and market opportunities for many european multinationals, including Spanish ones (something highlighted in the collective publication Javier Santiso ed., Las economías emergentes y el reequilibrio global: retos y oportunidades para España, fundación de estudios financieros, Madrid, 2011).

Europe and Spain have to rethink their relationship with emerging countries

This relationship has now become more symmetrical and balanced. Multinationals from emerging countries have also looked towards europe as investors. In the future, we will see more operations of this type in europe. In 2011, the Mexican firm Bimbo, the largest bakery in Latin America, bought the assets of its rival in Spain, for 115 million euros. One of its options could be to consider locating its international or european corporate headquarters in Spain, just like its compatriots cemex and Pemex. Arcor, the Latin American multinational has decided to locate its european corporate headquarters in Barcelona. There is no reason why other chinese, Korean or Brazilian groups could not consider doing the same. (for further Redding on this point, see Javier Santiso, La década de las multilatinas, Madrid, Fundación Carolina and Siglo XXI, 2011).

Moreover, why not imagine that Barcelona (which now is host to the World Mobile congress) could become a technological hub for the european corporate headquarters of emerging countries? At present, the chinese giants china Mobile, China Unicom and the technology companies such as Huawei, Lenovo and ZTE have chosen other european cities, mainly London or Paris. Why could Barcelona not become the future nerve centre of their operations in europe? Tencent, Baidu, Alibaba, and Renren are some of the more flourishing chinese start-ups (some are just behind Google and Amazon in terms of market capitalisation). Why not choose Catalonia for their european base?

This (new) trend also opens opportunities for Spanish multinationals and for Spain. emerging multinationals cannot only become financial partners but also they could also think about locating their corporate headquarters and european (or Latin American) industrial plants in Spain. europe and Spain have to (re) think their relationship with these countries. These are not only the challenges but also the opportunities that are appearing on the horizon.

The imperative of emerging countries for Spain

The perspective outlined here becomes even more necessary when we look at the decline of foreign investments in Spain. Lately we have seen how Spain’s fDI attraction factor has fallen. In 2009, the inflow of fDI only reached 15 billion euros gross, i.e. a fall of over 60% in comparison to the previous year. This decline is largely due to the global crisis affecting OecD countries since 2008. It is also because the reference points, 2007 and 2008, were record years for fDI in Spain. Still, the decline is greater than that recorded in other eU countries (-40% on average).

Attracting fDI, and even more so attracting corporate decision-making centres, is a market in which all countries are now involved. In europe, for example London, through its agency Think London, has become a hub for worldwide corporate headquarters, whether these be european, Asian or American multinationals. Hosts of Japanese companies like canon, Docomo, Ricoh and nomura have their european corporate headquarters in London. The global decision-making centres of global companies such as the Anglo-Australian Rio Tinto or BHP Billiton, the Anglo- Dutch Unilever or Royal Dutch Shell, the South African Anglo American and SAB Miller, those of Indian origin, such as ArcelorMittal and Vedanta, even have their global command centres, partially or completely, in the British capital.

In terms of finance, obviously most banks have european or international headquarters in the city, such as Goldman Sachs International and JP Morgan International. Recently, the city has attracted banks and investors from emerging countries, particularly from china, India, and even Brazil. Recently, the china International capital corporation Limited (cIcc) chose London for its european headquarters. The Singapore GIc sovereign fund has its headquarters for europe, Africa and the Middle east in the British capital. The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) has its main office outside its base country in London, as does the ADIA sovereign fund. The chinese cIc, which manages more than 200 billion dollars, is also considering London for its european headquarters.

In the race to capture the global, regional or european headquarters of multinationals, there are also many more european capitals contending, such as Paris (international headquarters of Microsoft), Luxembourg (world headquarters of Skype for example), or the different Swiss cities (world headquarters of the giant Glencore mining company for example). competition is fierce. Spain also has important agencies and instruments. However, a more ambitious strategy could be designed, with a Deputy Prime Minister of the Government, entirely dedicated to it. This person’s main duty would be to attract corporate investors and headquarters. They would devote the bulk of their time to meeting with chairpersons and CEOs in North and South America, Asia and europe in order to convince them to establish corporate headquarters in Spain and to make investments there. The measure of their success would be around this core objective (additional volume of fDI and the number of corporate decision-making centres). As in the private sector, to promote development and attract talent, the achievement or not of this goal would involve incentives.

What would the possible strategies involve? Three core groups could be considered as main targets: first multinationals from emerging countries in the process of internationalisation, second, european multinationals in the process of expanding into Latin America, and, finally, start-ups (in the sectors of technology, biotechnology, nanotechnology, renewable energies, etc.).

To select the first group, multinationals from emerging markets, focus could be placed on, for example, the 100 largest multinationals in these countries in the process of internationalisation as identified by the Boston Consulting Group. Some 500 of the largest corporations in Latin America identified each year in the magazine America economia should be added to this group. On the other hand, the quest to convince Indian or chinese companies to locate their european headquarters or eMeA headquarters in Spain will be particularly challenging. Spain has a comparative advantage with Latin American multinationals (See Javier Santiso, La década de las multilatinas, Madrid, Fundación Carolina y Siglo XXI, 2011). This is not to say that we should not rule out the Asian or even the Middle east multinationals.

In fact, some Spanish business leaders, such as the leader in the Iberian Peninsula of the Indian group Suzlon in the wind power sector, have their eyes on Spain to house their corporate headquarters for Southern europe and Africa. Imagine if the Philippine group owning San Miguel or chinese companies like Huawei and ZTE (with european headquarters in London and Paris respectively), which have one of their largest global customers in Spain, had similar notions. Similarly, the chinese oil company Sinopec, which has just joined forces with Repsol Brazil, could locate their european and Latin American headquarters in Spain. Moreover, why could the chinese electrical appliances group Haier not relocate its european headquarters from Varese, in Italy, to Barcelona or foton Motors from Moscow to Madrid? The chinese car company chery, which is looking to open a plant in europe and to expand into Latin America, could also choose Barcelona or Bilbao (where it has an agreement with the Bergé group). The Russian company Vimpelcom could likewise consider moving its headquarters from Amsterdam to a Spanish city, or its competitor Millicom (with several Latin Americans in its steering committee) could do the same from Luxembourg. Groups from the Middle East could also be considered, for example, the Saudi petrochemicals group Sabic or the Israeli pharmaceutical company Teva (both with european headquarters in the netherlands). The UAe multinational DP World, one of the largest players in port infrastructures in the world and with a presence in Spain (Tarragona) and Latin America, could relocate its european and Latin American headquarters, with the former currently in London and the latter in the US, to Barcelona, for example. Groups, sectors and executives, in particular, would need to be identified to trigger actions. In this strategy, Spanish multinationals that work or have partners in these countries could be key allies since some of them are important global customers or have international partners seeking to establish themselves in Europe.

There are examples of Latin American companies opting for iberian locations for their european centres

In this first circle, Latin American multinationals in expansion are particularly interesting. The truth is that there is a long way to go: in the end, in 2010 the Brazilian development bank, BnDeS chose London for its european office, as did Petrobras. The chilean firm Antofagasta, a subsidiary of the Luksic mining group, chose to set up its headquarters in London. The Argentine group Tenaris relocated its corporate headquarters to Luxembourg, while the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht decided to operate in europe, Middle east and Africa out of Lisbon.

Nevertheless, there are already examples of Latin American companies opting for Iberian locations for their european or international decisions centres. The most noteworthy are those of the Mexican companies Cemex and Pemex. The corporación Andina de fomento (Latin American Development Bank, CAF), an international financial organisation created by the states of Latin America, has also decided to open its european office in Madrid. Meanwhile, the Brazilian footwear company Alpargatas, the owner of the Havaianas brand, also decided to locate its european headquarters in Spain to gain a foothold in the entire european market. However, there is so much left to do: the Brazilian banks (Bradesco, Itaú Unibanco, Banco do Brasil) are undergoing international expansion processes and Spain could be a location for their european head offices. The same goes for Mexico’s Banorte, colombia’s Bancolombia and Venezuela’s Mercantil. The chilean or Brazilian sovereign fund might consider opening european offices and locating them in Spain. In short, Spain could become an entry point, offering eMeA (europe, Middle east, Africa) corporate head office locations for these multinationals.

A second circle could be added to this first circle of companies in a strategy of systematic attraction. This would include european companies with Latin American operations and headquarters. The EADS group, in which the Spanish government holds a stake, could very well, in addition to having CASA in Spain, install its Latin American operations in mainland Spain. The mining giant Xstrata, with corporate headquarters in Zug (Switzerland), has a Spaniard among its three top executives. Surely it might be thinkable for this group to install its Latin American headquarters in Madrid, a city infinitely better connected than the town of Zug? The finnish giant nokia has its headquarters for Latin America in Miami, why not in Madrid? It would be equally or better connected with the region and closer to the global corporate headquarters in Helsinki. Why could the British group BUPA (owner of Sanitas in Spain) not transfer its Latin American headquarters from Miami to Spain just as the German giant SAP has done? (In the case of BUPA-Sanitas, this appears to be taking place in 2012).

Just as Spanish companies could help attract companies in the first circle, they could also be very helpful here as many of them are probably the largest customers or partners in Latin America of such european groups. A third circle could be added to these first two, more connected to the world of start-ups and leading companies in particular sectors in the world of new technologies, new energies or biotech and nano-technology companies. Here, we would probably have to aggressively seek to attract talented and innovative entrepreneurs offering them tax levels worthy of football League players.

Spain could position itself as a port of entry for China in Europe

Spain and China

Above and beyond the general strategy outlined above, it can be illustrated with a specific emerging country just how Spain could further exploit the rise of this new world we are witnessing before our very eyes. far from being a threat, these countries provide opportunities. Spain’s relationship with Latin America is proof of this: if it were not for this continent, today the major companies in the country, or on the IBEX 35, would not be in the position to withstand to the crisis battering Spain and europe. Moreover, we are now seeing how they have become allies in many cases. The Qatar sovereign fund (Qatar Holding) entered in this way in 2010 and 2011 in the shareholdings of Banco Santander and Iberdrola, strengthening both companies. china’s Sinopec teamed up with Repsol, which also has Pemex as an ally. Meanwhile, the tycoon Carlos Slim has joined La Caixa. And there are many more examples from where these came from.

Apart from Latin America, Asia deserves special attention and in particular china. In the end, the rebalancing of the world that we are experiencing is largely explained by the rise of china. How can this shift help Spain and become a positive change for the country? The central idea is that Spain could position itself as a port of entry for China in Europe, providing a link between the two continents, just as it serves as a nexus between Latin America and Europe.

China has become an economic and political giant in recent years. International agencies have reflected this trend, making increasingly important gaps in their decision-making bodies, such as the International Monetary fund, or giving it key positions, such as that of World Bank chief economist. There is no global economical and political agenda in which today china is not essential. The boom in this country is undoubtedly one of the great global changes we are witnessing in the context of this massive redistribution of wealth and power towards emerging countries.

The visit of Li Keqiang, the then chinese Vice-Premier, to Spain in 2011 highlighted, once again, the growing importance of the Asian giant for all world economies, including those in europe and Spain. It is a paradox of history that the emerging economies, such as china, have now become a lifeline for many of the developed economies. Since the global crisis of 2008, there is no financial tour to sell sovereign debt that does not pass through Beijing. In the case of Spain, the visit reminded us that china already owns about 20% of the bonds issued by the Spanish Treasury, an amount equal to 43 billion euros.

This visit also invited us to consider the opportunity for Spain to establish a strategic relationship with china, positioning the country as a hub of entry to europe and Latin America for the Asian power. This is an idea about which at we have drawn up an Esade Position Paper published by the Esade centre for Global economy and Geopolitics, based on a meeting of Club España 2020, a platform that seeks to foster dialogue among senior managers located in the Spanish Peninsula and those outside the country holding key positions in many european and US multinationals.

Throughout 2010 and 2011, many chinese companies carried out major operations with Spanish companies. Such operations represent an opportunity to encourage some of these chinese firms to locate their european (and even Latin American) headquarters in Spain. for example, the Sinopec oil company bought a 40% stake in Repsol Brazil. BYD (Build Your Dreams), one of the world leaders in the field of electric batteries (which will be key for the electric car industry in the future), also signed an agreement with the Basque group Bergé for the distribution of its cars in Spain. On the other hand, the chairman of endesa and the chairman of BYD signed a partnership agreement. currently, another major chinese automotive group, chery, is also seeking to expand in europe and Latin America. In 2010, china decided to set up an industrial plant in Brazil. Likewise, the chinese entity IcBc decided to open branches in Spain to compete in retail banking. This is one of the largest chinese banks with nearly 400,000 employees and a market capitalisation that borders on 170 billion dollars. It has 18,000 branches worldwide and presence in 110 countries. The Spanish branch, for now, reports into the subsidiary of the chinese bank based in Luxembourg.

All these operations provide a window of opportunity for chinese partners to be able to locate their european (and/or Latin American) headquarters in Spain. To do this, concerted public-private action, between government and businesses, could be established. for now, chinese multinationals do not have any of their international corporate headquarters located in Spain, whether for europe or Latin America. Sinopec, for example, has several subsidiaries with offices in europe, mainly in London. It does not currently have an integrated headquarters for europe and/or Latin America. The deal with Repsol YPf presents a unique opportunity for this company to establish its european headquarters in Madrid, as another emerging multinational, Mexico’s Pemex, also a shareholder of the Spanish company, did years ago,. furthermore, owing to Repsol YPf’s links with Latin America, Madrid could also be the perfect place to locate its operational headquarters for Latin America.

The rise of the emerging markets constitutes both a challenge and an opportunity

In the case of BYD, the european subsidiary is in Rotterdam. Why not move it to Spain? In addition to facilitating expansion into europe, the BYD Spanish partners could offer expansion into Latin America by contributing their knowledge of the region. In 2010, BYD chose Los Angeles for its north American headquarters. The Bergé group also has extensive connections with Latin America. Why not locate not only the european headquarters but also the BYD Latin American headquarters to Spain. either Bilbao or Madrid could be home to its operational centres.

These are many more examples like these: the china Investment corporation, china’s sovereign wealth fund, which currently seeks an international headquarters in europe, the telecommunications industry providers, Huawei and ZTe, have their european headquarters in London and Paris, but one of its largest global customers (Telefónica) is concentrated in Spain; there is also the Hong Kong giant Hutchison, which has invested $400 million in the port of Barcelona and citic, the chinese strategic partner of BBVA, which has several subsidiaries, in particular those for asset management, could open offices in Madrid to distribute chinese funds in europe and even use this platform for Latin America.

Conclusion:

The rise of the emerging markets constitutes both a challenge and an opportunity. There is a great latent potential in this area. The crisis battering Spain with particular virulence is an invitation for us to reinvent ourselves. Spain has many tricks up its sleeves to reposition itself internationally. It has done so in the past with europe and more recently with Latin America.

A commitment to emerging markets is undoubtedly a strategy for success, as is that of europe. Spain here has the opportunity to position itself as a nexus, a bridge between the two. Many Spanish companies have masterfully opened themselves up to emerging markets in the past. Such connections become a strategic asset for the country to aspire to become a hub for the expansion of these multinationals from emerging countries, even from China.

Let’s not let this opportunity pass us by. churchill once said: “an optimist sees an opportunity in every calamity; a pessimist sees a calamity in every opportunity.” He also used to say, “never let a good crisis go to waste”. now, more than ever, we cannot throw away such an opportunity. It gives us a chance to change, to reinvent ourselves. Last year Steve Jobs passed away. In his speech in Stanford in 2005 he said, “Stay hungry, stay foolish”. As a nation, we should make this our motto.

In the oncoming years, from 2012-20, and in Spain in particular, we must remember these words. And this should inspire us to look even more than ever towards emerging markets, not only to Latin America but also to Asia, the Middle east and even Africa.

JAVIER SANTISO. Professor of Economics, ESADE Business School. Vice Chairman, ESADE Geo Centre for Global Economy and Geopolitics Twitter: @Javiersantiso